The Idea of the 3-rd Rome

After the fall of the Constantinople the Roman cultural and imperial heritage was always subject to disputes. The race for prestige and legitimacy was forcing different eastern or European monarchies and dictatorships to declare themselves as the new Rome or 3-rd Rome (Russian Tsars, Mussolini, etc.). And here we will try to show that it is the US that came closest to the pedestal of the 3-rd Rome, with its cultural, political, historical, geopolitical aspects.

Artistically, Roman aesthetics continued to impress Western sensibilities. Americans’ fascination with ancient Rome did not end during the founding or the early days of the new republic. It continued in the schools where Latin was taught. Rome is very much alive in American imaginations today. And the historical similarities make all this even bolder. The Romans went through a dramatic passage from somewhat “foreign” monarchy (Etruscans) to the republic — just as Americans at their funding, when they separated from an increasingly foreign British monarchy (The Georges recall were Hanoverians).

The comparison we are building can be divided into two historical cycles, the foundation of the US is compared to the Roman republic and the modern US (after the WW1 to Imperial Rome)

The Founders were thrilled by the fall of the Western Empire and took lessons from that fall and applied those in the American cause. They were especially concerned that luxury would lead to the undoing of the republican virtue. The founders imagined what a good empire would be like. – e.g., Jefferson’s Empire of Liberty was borrowed from the universal ideals of the Roman Empire. However, the Founders also warned that empires could injure freedom if there were few checks and balances. The dictatorial or absolute rulers who emerged during the Roman civil wars and the Roman Empire provided antimodels, examples of the hell people should never descend into. Many Southern aristocrats were identified with the ancient Romans because of the institution of slavery. Nevertheless, while building historical comparisons we have to keep in mind not only the historical differences but also the differences of the historical framework and the logic of time. Those comparisons can be built only on similarities of heritage or by philosophical approach and here by using the theory of the civilizational waves of Toynbee.

The Pax romana or the Roman peace was the eventual product of the international relations in antiquity, and one of the key factors for the followers to dream about. The role of Rome as the Global Dominant in the international relations forced all the political issues to be solved under the auspice of the Republic. This was transformed into what many scientists call Pax Americana or American peace, the nowadays condition of the IR after the collapse of the USSR.

Founding Fathers and the Roman influence on them

Ancient history provided the Founders with examples of behavior and circumstances that they could apply to their own reality. All of them were well educated people and the classical education was almost fully based on the Roman and Greek studies. Their heroes were the Roman republicans and defenders of liberty. All of the Founders’ Roman heroes lived at a time when the Roman republic was being threatened by power-hungry demagogues, bloodthirsty dictators and shadowy conspirators. The Founders’ principal Roman heroes were Roman statesmen: Cato the Younger, Brutus, Cassius and Cicero — all of whom sacrificed their lives in unsuccessful endeavors to save the republic․

They did not use Classical writing the way modern thinkers often do, as an Ultimate Authority to be unerringly obeyed. Instead, the statesmen who founded America treated those who founded Rome as equal partners in an ongoing debate. They challenged their ancient forbearers like college roommates haggling over a philosophy paper. That dialogue is the one building America. The political vocabulary they used — republic, virtue, president, capitol, constitution, Senate — had Latin etymology. The legislative processes they utilized — veto, sine die — were Latin. Many of their political symbols — the eagle, the fasces, the image of a leader on a coin — were Roman in inspiration (we will proceed with this discourse later).

The Founders’ and Framers’ noms de plume were Roman — Publius, Cicero, Cincinnatus, Cato, Brutus. They were consciously identified with Roman models of republican virtue. So:

- George Washington: others were calling him American Cincinnatus. While he preferred to call himself Cato the Younger,

- John Adams was called Cicero, the greatest attorney of the ancient world,

- Besides their differences with Adams, Thomas Jefferson was called Cicero too,

- James Madison was known as Publius (Valerius Publicola),

- Alexander Hamilton was most surprisingly identified with Caesar.

- John Jay, the first Chief Justice of the United States, was identified with Publius (Cornelius Tacitus).

While Rome served as a primary example of republicanism for the Founders as a whole, no one took it to heart more than John Adams. Adams, like Cicero, was a newcomer in the field of politics. He studied the Bible and the ancients, but nothing inspired him as much as the works of Cicero. Due to Cicero’s influence, Adams chose law as his profession. In fact, to prepare for his first case, Adams read Cicero’s orations, saying: “It exercises my lungs, raises my spirits, opens my pores, quickens the circulation, and so contributes to my health”. Adams dedicated his life to justice. He was active throughout the Revolutionary period, writing depositions against the Stamp Act and publically questioning the authority of the Parliament in Massachusetts. He also defended the soldiers who committed the Boston Massacre, a move that could have very well ruined his reputation. His defense of the truth of the matter, of protecting innocence even in the face of a mob clamoring for vengeance, earned him a reputation of seeking the truth in much the same way that Cicero earned his reputation in the prosecution of Gaius Verres. Adams later showed that he was an excellent judge of character, as a delegate to the First and Second Continental Congresses he nominated George Washington as a Commander of the Army and served in the committee that wrote the Declaration of Independence, nominating Thomas Jefferson to write the document himself. In 1780, Adams played a significant role in drafting the Constitution of Massachusetts, upon which the United States Constitution was largely based.

As Ambassador to England in 1787, Adams wrote his “Defense of the Constitutions of the United States of America” and sent it to his colleagues to help them collect votes. That came in handy: when Jefferson’s Declaration came down to a nail-biting vote, it was the powerful oratory Adams learned from Cicero that tipped the scales in favor of independence. In a two-hour speech, with Ciceronian flair, Adams convinced the Continental Congress to vote for revolution. Colleagues called Adams “the man to whom the country is most indebted for independency.” And later some added: “For the country that was born in Philadelphia that day, we have Adams — and Cicero — to thank.”

Following the Ratification, Adams went on to become the first Vice President of the United States and the second President. His Presidency was tumultuous to say the least, in which he secured peace with France following the intense military buildup during the Quasi-War. Adams also signed the incredibly unpopular Alien and Sedition Acts into law and thereby saved the early Republic from tearing itself apart. In his pursuit for the safety of the Republic, Adams sacrificed his popularity and was defeated in the election of 1800, just as Cicero fell from grace for going against public opinion. Both John Adams and Cicero proposed similar republican prescriptions for the political upheavals of their time. Yet while Cicero’s calls for reform went unheeded, Adams’ ideals found a political reality. The Ciceronian school of political thought has been studied for two millennia and found its culmination in the American Constitution, which John Adams influenced by his own constitutional work in Massachusetts and by his book on political theory at the time of the Constitutional Convention. Cicero gave Adams the idea of “a mixed constitution of three branches” each restrained by a delicate equilibrium of checks and balances. Adams adopted that concept in his Defense of the Constitutions, which guided the framers as they wrote their own founding document — the one America upholds today. There can be no doubt that Cicero’s republican ideology found its way into the American Constitution and that the liberties people enjoy today have their roots not in an inspired gathering of the Founding Fathers, but in a more ancient time, in the Republic of Rome. We mostly talked about Adams and Cicero since they are the most striking examples of the similarities, but as we see, there are more analogous “pairs”. And they all lead us to the conclusion that all these nicknames and noms de plume were not just aimless eponyms they were the results of ideological similarities and sheared legacy.

Above all the story of the ratification of the Constitution of the United States of America is one of freedom from tyranny, of reason triumphing over anarchy, and of a daring experiment in government by a fledgling nation. The Founding Fathers set forth a new form of governance in which the sole purpose of the state is to legislate in favor of the people, not shackle them in the chains of oppression by the whims of a few ruling elites. This system, this republic has been hailed for centuries as a turning point in human history for creating a stable government that works in the interests of every citizen in the nation. The Fathers especially revered Cicero for his ardent patriotism, poisonous contempt of demagogues, and extensive dialogues on philosophy and statecraft, for this reason, his ideas figured prominently in the political theory undergirding the Constitution. The republican ideals of Cicero heavily influenced the generation of the Founding Fathers in favor of a mixed constitution. The works of John Adams, the unsung hero of the era, brought Ciceronian republican prescriptions to the forefront of the American political thought at the time of the Founding.

The influence of Cicero through Adams ultimately shaped the structure of the American Constitution and brought about the birth of the American Republic.

The ideological similarities between Rome and the US from the perspective of law and citizenship

Alexander Hamilton, an astute student of classical history, devoted his first contribution to The Federalist Papers to a warning against tyrants or “men who have over-turned the liberties of republics, commencing as demagogues and ending as tyrants.” This education aided in their ability to understanding history and bringing out a new political system. The resemblance between the Ancient Roman Republic and America’s political system is uncanny. America’s advent of the executive, judicial, and legislative branches were directly derived from the Ancient Roman model.

- Executive Branch

In times of peace, the executive branch of the ancient Rome comprised two consuls, elected by Roman landowners for 1 year terms. At all times, the executive branch also contained various bureaucrats who were in charge of arranging festivals and conducting censuses. The same system was used in The USA, President, & Vice President similar to the two consuls and the government similar to bureaucrats.

- Legislative

The most influential members of the legislature in Rome were those in the Senate. This large body of elected land owners decided how state money was spent and what projects were viable for state funding. The Senate also took control of foreign policy in particular, the many wars Rome was engaged in as it expanded its territory. In this case similarities are more than obvious, the modern US Senate generally speaking has the same role and rights as the ancient Roman, even the name of this institution was not changed. By the way, today very often Senators are nominated and elected as presidents just like it was with the counsels in Rome.

- Judicial

The judicial branch of ancient Rome was very similar to the modern US courts (however we have to admit that the judicial branch in the US bears some significant influence of English law), particularly the Supreme Court of modern-day America. Six judges were elected on an annual basis to administer the law of the land to those who broke it. Unlike the judges in the modern US, the Roman judiciary could actively create sentences and punishments instead of merely following the past precedent or the sentencing law handed down from the legislative and executive branches, however the right of the constitutional court to interpret the constitution and the laws is somehow the transformed form of the creational jurisprudence of Rome.

The citizenship and professional armies are another remarkable similarity. The Citizenship of Rome was the prototype for the “New” idea of equal and free citizens in the US. The citizens in both places have rights that are differentiating them from the rest of the world in the eyes of the state. And last but not least, the first model of the professional army much before it was created in the US was the Roman Legion.

Roman symbolism in USA

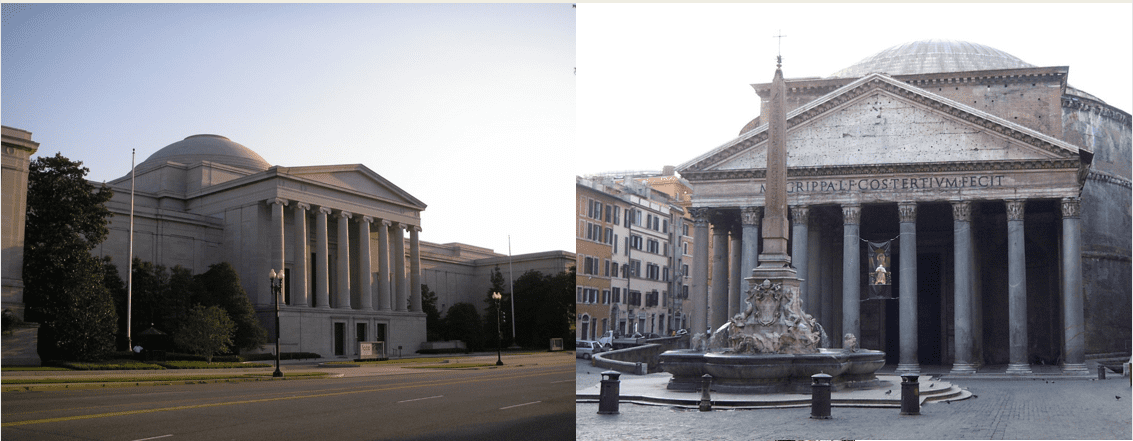

The architecture of the American founding also showed a predilection for the Roman aesthetic sense. It is not too much of a stretch to assert that the buildings and monuments lining the National Mall in Washington, D.C. with their stately, classical architecture might resemble a Roman colony.

Some perfect examples are listed below:

- Perhaps the most obvious example of this lies in the Supreme Court building. Cas Gilbert’s design draws its inspiration from Roman temples. The staircase, raised podium and the columns would not be out of place in the Roman Republic. Similarly, the white marble on the Supreme Court and throughout Washington, D.C., was consciously selected to mimic the architectural splendor of ancient Rome.

- The Capitol, White House, Thomas Jefferson’s memorial were loosely based on the Roman Architecture.

The same logic works not only in architecture but also in arts and symbols of the time of young American republic:

- The Founders’ sculpture and painting were also inspired by Roman precedents. It is not unusual to see them adorned in a toga.

- The Roman Eagle was transformed into the great seal of the USA.

The US Capital is identified even with Rome’s geography. In Washington, D.C., Capitol Hill (formerly called Jenkins Hill) alludes to one of the Seven Hills of Rome. Almost all political and law terminology was also copied from the Latin roots.

At the end another aspect should be mentioned – the Law. After the fall of Rome, the US became the first state to be fully led by laws. After the fall of the ancient world the idea of the rule of law was forgotten and the Term “right” was used only with some religious context. The US became the first modern state to be fully governed by elected authorities. The idea of a civilized society where no one is higher than law, where all interpersonal relations can be regulated by law where the state wasn not affiliated with certain people but rather with a system (together with above mentioned) was the renaissance of Romanism. The idea of the land of civilization that was dominant in Rome transformed through the civilizational waves of Toynbee into the idea of land of freedom that Americans use about their country.

Therefore, the American Republic is hardly a new idea and is in fact a mere innovation of a far more ancient political system: The Roman Republic.

Bibliography

- Առնոլդ Ջ. Թոյնբի, Հասու լինել պատմությանը, Երևան, Անտարես, 2013

- Appian, The Civil Wars,

http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/e/roman/texts/appian/civil_wars/1*.html, (01.06.2017)

http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/e/roman/texts/appian/civil_wars/2*.html, (01.06.2017) - Cicero, On Obligations, trans. Walsh P., New York, 2000.

- Cicero, the Orations of Marcus Tullius Cicero, In Catilinam,Yonge C., London, 1896.

- Cicero, The Orations of Marcus Tullius Cicero, The Philippics, trans.Yonge C., London, 1903.

- Cicero, the Republic and the Laws, Rudd N., New York, 1998.

- Dio Cassius, The roman history

http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/e/roman/texts/cassius_dio/home.html, (01.06.2017)- The Selected writngs of the founding fathers and the constitution of the United States, New York, Barnes And Noble, 2012.

- American Founding: Roman Influence,

http://hauensteincenter.org/american-founding-10-roman-influence/, (01.06.2017) - Adams J., The Life and Works of John Adams 4, Boston, 1851.

- oe Wolverton II, The Founding Fathers & the Classics,

https://21stcenturycicero.wordpress.com/tyrrany/the-founding-fathers-the-classics/, (01.06.2017) - McCullough D., John Adams, New York, 2001.

- Richard C., Greeks & Romans Bearing Gifts: How the Ancients Inspired the Founding Fathers, Lanham, 2008.

- Richard C., Why we’re All Romans: The Roman Contribution to the Western World, Lanham, 2010.

- Sellers M., American Republicanism: Roman Ideology in the United States Constitution, New York, 1994.

- Spencer Klavan, The American founding fathers and the classics https://classicalwisdom.com/ancient-bickering-founding-fathers-knew-classics/, (01.06.2017)

Author: Areg Kochinyan. © All rights are reserved.