Enlight Studies together with Utblick Göteborg start an article exchange collaboration as a testimony of mutual learning, practice exchange, and stimulating analytical thinking.

By:Ida Flik.Originally published at Utblick

The sea between Northern Africa and Europe continues to be the by far the deadliest border, accounting for over one-third of all migrant deaths recorded worldwide. In 2019, about three people died every day on average in attempts to cross the Mediterranean.

Meanwhile, state-run operations are moving further away from rescuing people and instead, are focusing on securing EU borders.

In 2013, after over 600 people drowned in front of Lampedusa, Italy started a sea rescuing mission: “Mare Nostrum”. One year later, it was cancelled and replaced by Triton – a program that was not only much smaller but also run by Frontex, the European Border and Coast Guard Agency, which is tasked with border control of the European Schengen Area.

In May 2015, the EU added an anti-smuggling “European Union military operation in the Southern Central Mediterranean“, which became known as “Operation Sophia“.

While both Triton and Operation Sophia (officially EUNAVFOR MED) were never primarily search-and-rescue missions, their ships did rescue people in distress if they encountered them on their missions, as they are bound to by international maritime law. However, in recent years, these EU-powered ships are kept closer to the Italian coast, usually within 30 kilometres from the Italian territorial waters. This is far away from where most ship-wrecks occur: close to the Libyan coast.

Part of Operation Sophia’s anti-smuggling efforts was the destruction of smuggler boats, which was found to only lead migrants to embark on Mediterranean crossings with even less safe boats. The operation was also sharply criticized for funding, training and cooperating with the Libyan Coast Guard, who are staffed by several militias, and who are regularly accused of severe human rights violations. [1] [2] [3]

Operation Sophia was discontinued in March 2019 because Italy threatened to block the efforts “on the grounds that rescued migrants were almost exclusively brought to Italian ports”.

Today, the EU (and Italy in particular) increasingly transfer responsibility for a safe sea to Libya. Libyan coast guards, in turn, have been reported to be unresponsive to calls for help and allegedly have ties with smugglers and forced labour camps. The EU nevertheless funded and helped Libya build the infrastructure to formally take on the responsibility of a large part of the international waters between the Libyan and Italian coasts. In June 2018, the UN’s International Maritime Organization officially acknowledged Libya’s declaration of this widened search-and-rescue (SAR) region.

Human Rights Watch commented on this: “Enabling Libyan coast guard units to intercept people in international waters, when it is known the coast guard will return people to cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment in arbitrary detention in Libya – conditions that have been well-documented – may constitute aiding or assisting serious human rights violations“.

Furthermore, in August 2019, an international investigative unit uncovered a £95m EU investment into unmanned drones. The Guardian article reads: “This spending has come as the EU pulls back its naval missions in the Mediterranean and harasses almost all search-and-rescue charity boats out of the water. Surveillance drones operated by Frontex, or by agencies or service providers with which Frontex co-operates, appear to be flying over waters off Libya where not a single rescue has been carried out by the main EU naval mission since last August, in what is the deadliest stretch of water in the world.”

Criminalization of civil sea rescuing missions

Civil society actors in both newly founded as well as established NGOs started responding to the lack of state-run rescue missions on the Central Mediterranean as early as 2015 by buying or leasing ships to run their own missions. These donation-funded, volunteer-run crews searched for people in distress and helped them reach safe harbours, as obliged by international maritime law.

At times, 16 of this civil Search-and-Rescue (SAR) boats were out in the Mediterranean. Many of them were small boats, incapable of taking dozens of people on board or transporting them to a safe harbour themselves. Usually, with the help of the Maritime Rescue Coordination Centre (MRCC) in Rome, a bigger ship would be sent or de-toured to take the rescued people on board, while the NGO boats would provide life jackets, water, and first-aid medical care if needed and continue their monitoring once the rescued people were headed off towards European mainland.

The cooperative relationship between NGO missions and state authorities changed as the European right-wing and their anti-immigration views gained power. In the summer of 2017, all civil SAR organizations operating in the Mediterranean were pressured to sign a Code of Conduct, which amongst other things prohibited NGOs from transferring migrants to other boats. Transporting ship-wrecked migrants to the shore themselves would have cost them days worth of further monitoring presence on the water, where at times, over 700 people had to be rescued each day. Considering that most NGO ships are small and don’t have capacities for transporting dozens or hundreds of people, following this code of conduct would have rendered their work impossible.

Those who did sign the code further agreed to have police officers on their boats. These measures treated search-and-rescue NGOs as potential criminals alongside smugglers; rhetoric which according to Buzzfeed news partly “comes from a revised 2014 Frontex report that stated SAR vessels were a “pull factor” for refugees. But the report itself was revised after it was leaked, and its conclusion was disputed.”

Jugend Rettet, a German NGO, saw their ship Iuventa seized only days after they had refused to sign the code of conduct. The Iuventa had come under the Italian Secret Service’s scrutiny after agents of a contracted security firm (who were later suspected of ties to the far-right “identitarian” movement) onboard another ship claimed to have proof of them cooperating with Libyan smugglers. The legal proceedings have been criticized because of “legal irregularities and gaping holes in the prosecutor’s narrative” and Forensic Architecture from Goldsmith’s College released counter-evidence and findings of their investigation. The seizure was confirmed in April 2018.

SOS Mediterranee’s “Aquarius” had to stop operations already in November 2018 after the Italian government pressured the Panamanian state to withdraw the flag of the ship. 24 staff members were still under investigation from Sicilian authorities for “illegal management of waste” as of June 2019. 10 crew members of the before-mentioned Iuventa continue to be investigated and risk up to 20 years in prison.

Two ships belonging to the organization “Sea-Eye” also stopped operations after Dutch authorities withdrew their flags.

The NGO Mission Lifeline saw their ship seized a few months ago and are now working on getting a new one to be in operation again by May 2020 the latest. In an interview, their spokesperson Axel Steier mentioned the political dimension of regulations and the interpretation of the law: “The states confiscate the ships on whatever legal basis. […] They interpret the legal frameworks as they want to.”

For example, German authorities place high technical standards on operators of ships exceeding a certain size, which makes it costly and time-consuming to maintain ships with a German flag. The Netherlands used to have looser regulations for ships up to 400 gross registered tons (GRT), but have now introduced new regulations that require higher technical standards, as well. Steier mentioned that other organizations such as Greenpeace and Sea Shepherd, who are not active in the Mediterranean, have many of their ships registered in the Netherlands as well and will be affected by these new regulations.

In 2019, Salvini closed the Italian harbours for NGO ships with migrants on board. This leads to ships with sometimes over 100 people on board waiting for days or weeks, while European politicians discussed how many migrants on board different countries and cities would allow in. In some cases, captains declared an emergency state onboard and entered harbours, ignoring the coastal authorities’ orders. Captain Carola Rackete was arrested this summer after entering an Italian port against orders from a military vessel. Investigations are ongoing.

Both Mediterranea’s “Mare Jonio” as well as Mission Lifeline’s “Eleonore” were confiscated by Italian authorities in September 2019 too. In both cases, fines of 300.000€ were issued against the captains for entering Italian ports, with dozens of migrants on board.

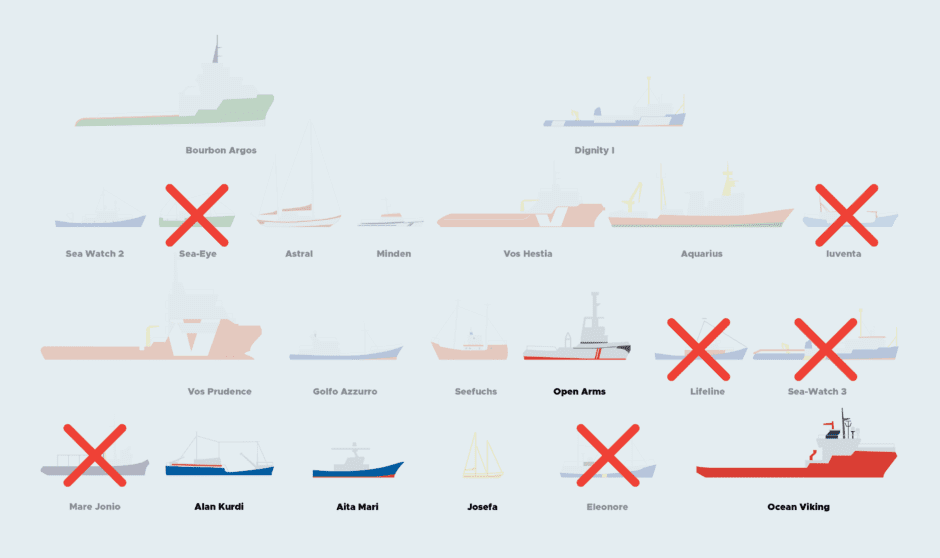

Blurry = not operational any more

Red cross = seized or otherwise legally prevented from operating

Full-colour = operational

In June 2019, the Italian government under right-wing interior minister Salvini announced legislation that could fine sea rescuers with up to 50.000€ for bringing migrants onshore. In August, new laws were added that increased fines to 1 Mio € and decided the automatic impoundment of vessels. Resistance to Italian security forces’ attempts to block rescue ships from entering a safe harbour is punishable by up to ten years in prison.

In December 2019, only 2 out of a total of 24 NGO ships were running missions in front of the Libyan coast: The “Alan Kurdi” and “Ocean Viking”. Two other rescue ships, the “Open Arms” and “Aita Mari”, were operational at the time but not allowed to leave Maltese waters, according to Steier from Mission Lifeline.

Steier concludes: “When it comes to pushing through their migration policy interests, EU states don’t mind using even illegal means, like financing the Libyan Coast Guards. […] Those who financially contribute to human rights violations are responsible for them, but they don’t care.“ [quote translated by the author].