Japanese manga is considered to be “one of the main cultural manias” for decades and wins huge popularity not only in Japan, but also outside its borders. Manga being prominent by its stylistic and thematic varieties is a story that is published in black and white format (7.5 x 5 inches) and is read from right to left and from top to bottom. It introduces people to the Japanese culture i.e., food, clothing, traditions, feasts becoming not only a method of entertainment but also the visiting-card of Japan.

Conceptionabout manga in Japan and outside its borders, however, are different enough. Outside Japan, including Armenia, many misunderstand that Japanese mangas are childish stories based on friendship, constant fights (especially Ninja battles) and heroic ideas. This is mostly due to the fact that only a small part of manga published in Japan is available in English and other languages, and the acquaintance of people to manga outside Japan is directly interconnected with the animes based on manga e.g., Dragon Ball, Naruto, Bleach and also with the popularity of the other stories.

Are its roots laid in the early Japanese art or, however, manga is a present-day phenomenon that has been formed by the influence of the West? Only clarification of these contradictory perceptions will allow to understand the uniqueness of Japanese manga by which it crosses cultural borders of many countries.

Historical Distribution and Popularization of Manga

Japanese manga has rich history and originally comes from the twelfth century, the Buddhist monks’ illustrated books. The most known examples of that art, such as “Caricatures of the animals”(Choju Giga), are the famous manuscripts that portray the animals behaving themselves like people in different situations.

There are also similarities with another type of the graphic novel emerged in 16-17 centuries, the Ukiyo-ei.e., the genre of painting and typography done on textile and then on the paper. Just like contemporary manga, it contained caricatures, bloody fights and erotic scenes as well.

Almost at the same period, in the eighteenth century, Kibiyoshi or The Yellow Books got widely spread that were humorous, satirical and were mainly to mock the Japanese statesmen.

The word “manga”, however, started to be used only in the nineteenth century by the famous artist Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) who circulated the word “manga” in order to characterize his book of patterns published in 1814. The word itself is of two components: “man” which stands for “unwittingly” and “ga” which is translated as “pictures” (although initially Katsushika had used the word “man” as “whimsical”[1]).

Katsushika Hokusai, “The Buddhist Monks“, Haokusai’s manga, 1814

It’s obvious that all the types of graphic art have stylish similarities with contemporary manga but, in this regard, the Western culture also hasn’t played a less important role.

The influence of the West on manga energed in the Meiji period (1862-1912) when Japan opened its doors to the West. As a result, Japan got acquainted to the European and American Comics thanks to the foreigners and set up on contemporary manga gradually combining those special elements to their graphic style. In that period the Japan Punch was published, the first humorous magazine in the Western style. It has been getting published from 1862 to 1887 in Yokohama by the British artist Charles Wirgman. In the magazine funny sketches had taken a place about how people, arrived from the West to Japan, found it difficult to make commercial and diplomatic contact with the Japanese. The magazine had a big influence on the Japanese artists and writers who were worried in the beginning about the influence of the West on the process of modernization of Japan. The latter, in its turn, started publishing posts mocking the policy of the Japanese government.

By the 1920s two types of comics were widespread.

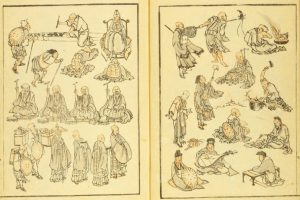

Children’s comics inserted in the newspapers and magazines that the parents bought for their kids. Those posts had mostly borne the influence of the American comics. Furthermore, the translations of the American comics were inserted in them, stories such as George McManus’ “Bringing up Father” or Pat Sullivan’s “Felix the Cat”, also the Japanese comics based on American/European patterns, such as “The Adventures of Little Show”.

In a number of short political images for adult readers e.g., the publications “Workers’ News” (Musansha Shimbun), “War Banner” (Senki), the influence of Marxist ideology felt.

This separation between manga provided for children and adults maintained in the future as well becoming one of the long-lasting characteristics of the manga industry.

World War 2 has been pivotal for development of manga taking into account that manga has got its present-time look and design only after World War 2. In the early post-war period manga succeeded as a way of cheap fun for Japan that was tired of the war. This time too (in the years of occupation in Japan, 1945-1952) manga was evolving by the influence of the American comics. Famous headlines such as Blondie, Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck and Superman were published in Japanese translation.

In the beginning of post-war period manga was published in three main ways:

Presentation with images (kamishibai)- In 1946-48 theatrical performances based on cards with images were staged all over Japan. Using those cards the teller was reading them and presenting with theatrical sketches. Those performances gained a great publicity until the beginnings of 1950s.

Mangas for rent (kashihonya)- The second type promoting the contribution of manga was the establishing of the shops of renting books which made manga available for the wide frames of community. The mangakas (manga writers) wrote for books and magazines that could be rented with ¥10 for two days.

Manga books (yokabon)- They were small books that were sold in discount bookstores (zokki) and stores for baby toys and costed about ¥15-20[2].

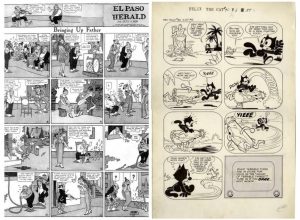

The production of manga reached a new level in 1950-60s thanks to Osamu Tezuka who is known as “the Godof manga”. His “Ambassador Atom” which was renamed as “Astro Boy”later, played a pivotal role in development of manga. In the future a line of homonym anime-series was shot becoming the first widely recognized Japanese animation TV series. Very quickly,”Astro Boy” became (and remains) a very lovely character not only in Japan but outside its borders as well.

Thanks to “Astro Boy” the anime[3] format also reached a new level in Japan. In the basis of anime widely known manga stories started to be used which, however, doesn’t mean that the opposite is not possible. Its proof is Pokémon originally was a computer game and in the future it was published in another media format, including in the type of manga.

In the 1980-90s manga became mainstream and was read almost by all the age groups. In this period manga got expanded in the world market. But it couldn’t be imagined without anime which was strictly interconnected with manga in the case of worldwide spreading of the Japanese visual art.After the broadcasting of “Akira” (1988 in Japan, 1989 in the USA) and “Ghost in the Shell” (1995 worldwide broadcasting) (both are based on manga) Japanese anime and manga both started to get attention from the world audience more than ever.

In the beginning of 2000s the manga industry stopped to specialize only in the Japanese publishing companies (Kodansha, Shueisha, Shogakukan). Small transnational manga providers and publishers too (Tokyopop, Viz Media and Seven Seas Entertainment) were set. These upgrowths also led to the emergency of OEL (Original English-languages) manga which was made by the non-Japanese artists. Manga moved to the online dimension as well which allowed to expand their audience more. From this point of view, there are important sites such as www.mangafox.com, www.mangapanda.com, that make translated versions of the manga stories available and, furthermore, the translations are almost synchronized to the publishing of the original.

What about “the official recognition” of manga, the opening of Manga faculty in Kyoto Seika University in 2006 speaks which was the first one of its kind.

Distribution of Manga in Armenia

The traditions of Japanese manga and anime in Armenia are relatively new. The acquaintance to the Japanese graphic culture started in the 1990s. Initially the Armenian audience (mostly children and teenagers) didn’t distinguish anime from another cartoons, and it was supposed that it was for kids, and about the existence of manga was known by few ones. It was mostly because the anime TV series e.g., “Sailor Moon”, “Candy-Candy”, “Pokémon”, “Maple Town”[4] were for the 12-18 year-old audience.

Today in Armenia the main audience of Japanese anime and manga is formed of 13-28 year-old people taking into account that the audience acquainted to anime still being child in 1990s is already adult and discovers other genres of anime and manga that is for more mature age group.

It should be noted that anime got massiveness in Armenia probably only in the 2000s with spreading of anime series “Naruto”, and the acquaintance to manga started due to the accessibility to the internet and social network. Today we can find manga books in bookstores although the market is still small, and in the different social networks, especially on Facebook and VK, Armenian versions (mainly the translations of the fans) of different animes and mangas are available, also there are a big amount of fan pages where the fans exchange with impressions and opinions about either anime or manga.

Thus in Armenia, too, the word “manga” started to be perceived and used as a description of a comics published in Japan but, as it was noted before, those perceptions are different enough in Japan and outside its borders: in Japan manga (kanji:漫画; hiragana:まんが; katakana:マン[5]) characterizes both comics and cartoon while outside Japan it’s used solely for the arrangement of graphic novels published in Japan.

Typology and Main Features of Manga

Manga has more than 30 genres and subgenres (horror, detective, comedy, historical drama, etc) that vary by their style and content and discover the diversity of the readers and thematic encompassing of manga. The bases of segmentation are plenty but one of the biggest separations is the one based on age and sex e.g., Shonen (for boys under the age of 18), Shojo (for girls under the age of 18), Josei (for adult women, girls), Senien (for men). More details are shown in the chart.

The Typology of Manga. Main Types

Kodomomuke manga is a “nicer” graphic style for kids. Initially it was affected by the Disney cartoons and comics, especially after World War 2. More famous examples of Kodomomuke manga are Osamu Tezuka’s “New Treasure Island” (Shin Takarajima, 1947) and “Astro Boy”(Tetsuwan Atomu, 1952-68)

Shonen Manga- Manga style aimed at boys under the age of 18 which has a huge genre diversity e.g., sports, science fiction, horror etc. The leading role players are basically males. Shonen manga got very popular in the 1960s. It is published mostly in specialized magazines (Shonen Jump) and is republished in the tankōbons[6] (with individual volumes). Some of more famous examples of Shonen manga are “Dragon Ball” (1984-95), “Slam Dunk” (1990-96), “Naruto” (1999-2004).

Seinen Manga- Is marketed toward adult men. With its genre inclusion it’s like Shonen manga (sports, politics, science fiction). More famous examples of Seinen manga are “Berserk”, “Ghost in the Shell” (1989-1990).

Shojo Manga- Is aimed at girls under the age of 18. It covers all the styles, from historical drama to science fiction. Shojo mana has matured in the 1970s. One of the most successful shojo artists is Takeuchi Naoko, the author of “Sailor Moon” (1992-97). Just like shonen manga, shojo is published in specialized magazines and is republished in the tankōbons too.

Josei Manga- Is aimed to adult girls and women and is like Shojo manga with its main features. Some of more famous examples of Josei manga are Yun Kōga’s “Loveless” and Ai Yazawa’s “Paradise Kiss”.

Gekiga

The word is of two components, “geki” which is translated as a theatre and “ga” a picture[7]. Thus “gekiga” means theatrical manga with more skilled and realistic characters. Very quickly the term got realized by the Japanese artists who didn’t want that their works were not identified with manga. Gekiga differs from ordinary manga with not only its plot, but the painting style too. In the 1960s kids who had been reading postwar mangas were no longer juveniles and had requirement of manga based on new, more realistic stories with real characters. Unlike the format of postwar manga, the characters of Gekiga are not always immortal and have life limits. Gradually the death theme got imported in Gekigas. In this style “Ninja Bugeicho (“Secret Martial Arts of the Ninja”, 1959-62), “Kamuiden” ( 1964-71) are the special ones.

Beside the genre diversity, Japanese manga is different with its structure and format. Manga got its present-time appearance only after World War 2. Traditionally it was published in black and white format not on the most qualified paper (based on economy status and resource restrictions) and it maintains its look till now though it also can be found illustrated pages in the beginning or the end of manga. And what about the structure of contemporary manga, the role of Osamu Tezuka is priceless here. Osamu Tezuka set considerable changes in the world of manga until his death (1989). According to Natsume who does researches of Tezuka’s works, the most remarkable revolution set by “the God of manga” was the changes of the panels of manga, their ranking and the harmonization of characters as well. Before Tezuka, no matter it’s about manga consisted of 4 panels or longer stories, the reading method was unified. The first must-read panel was always above the right corner, later you have to go down along the column, then pass to the left part, just like in Japanese books that are read from right to left and vertically from top to bottom, unlike Western books, from left to tight, horizontally. But Tezuka acknowledged that by its visual effect manga is closer to a film than literature. So he inserted the technique of horizontal painting in manga beginning from the right upper corner directing to the left upper part in horizontal way. After spreading of this idea Tezuka changed sizes of the panels in order to be possible to emphasize more important scenes, to increase the level of accuracy of manga and to insert the design of three-dimensional body shapes.

Thanks to him heroes with big eyes like Disney characters and charming faces which is one of the main features of manga. In manga the characters are more realistic and humane. They have their own character features, charisma, characteristics which lets the reader follow the character’s progress, understand their feelings and perceive them as real humane characters.

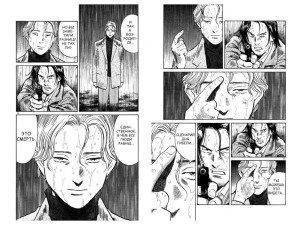

In Japanese manga the textual component is less than in comics. The main emphasis is on the visual images (it’s easier and faster to read, 3.75 seconds per page on average[8]) from which the content of fiction doesn’t suffer. All this is best shown in Naoki Urasawa’s “Monster”.

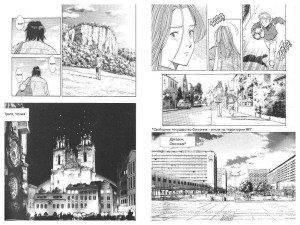

“Monster” of which story and illustrations are made by Urasawa, had been publishing in Big Comic Original magazine in 1994-2001. This manga has a hue thematic inclusion e.g., crimes, medical ethics, children psychological traumas, brainwashing, psychological experiences, humanitarian love, a period of Nazi Germany and the Cold War. The main hero is Kenzo Tenma, the Japanese neurosurgeon who lives and works in Düsseldorf, Germany, but had to chase a young psychopath named Johan whose life he saved as a doctor back in the times. These two characters consider the opposite poles of the story: from one hand, it’s Tenma who acts believing that all the human lives are equal, on another hand, here is Johan, according whom, people are equal only in front of the death. Urasawa wonderfully conveys emotions such as loneliness, anxiety, anger.

Urasawa’s painting skills astonish not only with the heroes’ too realistic images, but also with the 1980-90s’ reproductive accuracy of German and Polish cities and architectural structures.

Combination of visual and verbal components let Urasawa transfer the characters’ viewpoints, feelings, dreams and even thoughts clearly showing that the characters’ images speak by themselves just like in a movie.

The majority if his stories end up with doubt and the artist leaves doing of conclusions for the reader. And so is in the case of “Monster”. In the whole story it felt like that the Monster was Johan but every next chapter of manga and especially the last one, harbored doubts about who was the real monster, Johan or his mother, or each of the characters.

Thus though manga has a long-lasting story of progressing and reaches to the 12-13 centuries, but has got its present-time look and design only after World War 2, which is usually a reason for contradictory perceptions about manga. And here, outside the borders of Japan, manga became popular starting from the 1980s mostly thanks to anime. And taking into account that in Armenia too our acquaintance to manga most usually starts with watching of manga-based anime and it’s impossible to observe the distribution of manga without the interconnection of anime, as a conclusion, there are shown 3 masterpieces of Japanese graphic art that are worth knowing in both anime and manga formats. They are

“Neon Genesis Evangelion”

“Fullmetal Alchemist”

“Monster”

References

Bibliography

Author: Heghine Aleksanyan© All rights are reserved.

Translator: Christine Bdoyan