Introduction

Migration, and in particular out-migration, is a familiar phenomenon in Armenia. From the expulsion and execution of Armenians by Ottoman Turks in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, to oppressive conditions in the post-Soviet era, and the constant movement of diasporan Armenians, we see just a few examples of how Armenia’s political, economic, and social factors affect demographics and population stability.

Currently, about 2.9 million people live within Armenia’s borders and about 8 million Armenians live around the world (Gevorkyan et al., 2008). According to the 2018 Integrated Living Conditions Survey implemented by the Armenian Statistical Committee, 130,900 individuals (59.8%) left their place of residence and did not return (i.e. emigrated) in 2018 (ARMSTAT, 2018). According to a recent article published by Eurasianet, in 2021, 43,874 more Armenians left the country than entered (Mejlumyan, 2022). In the past 4 years, Armenia has seen a population decrease of about 6% (World Population Review, 2022).

The largest portion of Armenians wishing to leave the country are primarily young people and/or workers (ETF and CRRC Armenia, 2012). This has major impacts on an already thinly populated country, since those wishing to leave are at the “most active reproductive and economic age” (Barsoumian, 2013). It is clear that continued emigration poses a major threat to the nation’s development.

Who is leaving and why?

Several events that occurred in Armenia over the last few years, including economic decline from the Covid-19 pandemic and the 2020 Artsakh war, have led to higher emigration rates from the country (Avagyan, 2021). Increased economic hardship from the pandemic, political volatility from the war, and a general sense of worry have increased people’s desire to leave Armenia. While it is well documented that such economic and political instability contribute to waves of emigration, data on the particularities of individuals’ motivation to migrate are very sparse. A handful of sources such as the National Statistical Service of the Republic of Armenia’s Integrated Living Conditions Survey (ARMSTAT and the World Bank, 2018), administrative data from Border Management Information System (Manke, 2012, p.33), and research from international stakeholders such as the World Bank (Vidal, 2019) shed light on descriptive information about people entering and exiting the country. However, knowledge on the subject remains quite limited.

In order to combat large emigration flows, the influences and reasons for emigration must be understood. Current population data provides certain insights, but we can go even deeper by also trying to understand the qualities of the population who want to emigrate. By examining these trends, it may be easier to predict and analyze indicators of out-migration. We can begin to ask the question: why do people want to leave? And who is leaving? Data from the Caucasus Barometer, a bi-annual household survey about social economic issues and political attitudes conducted by the Caucasus Research Resource Center, can shed some light on these questions (CRRC Armenia, 2020).

Overview & Methodology

The Caucasus Barometer is a bi-annual household survey (n = 1,491) administered in three countries of the South Caucasus: Armenia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan [1]. The survey mode is a multi-stage cluster sampling with preliminary stratification and the population selected are adults 18 years old and above. The interviews were presented in Armenian through computer assisted personal interviews (CAPI). The fieldwork dates of data used in this research are from February 21, 2020 to March 15, 2020. The survey question that indicates the respondent’s desire to emigrate is “if given the opportunity, would you leave for good?” (EMIGRAT variable).

The following data analysis was completed using Pearson’s Chi-Squared test on EMIGRAT and other variables in the dataset.

Out of the individuals surveyed (excluding NA’s and those who answered “don’t know”), 22% of respondents answered that they would choose to live somewhere else if they could, and 78% chose to stay.

Compared to Georgians, in 2021, only 12% of Georgians wished to emigrate while 88% chose to stay. In comparison, nearly double the proportion of Armenians surveyed wished to leave for good.

Today, many studies show that the largest population of emigrants from Armenia are those leaving for short-term, seasonal labor, and most migrants are males traveling to Russia for higher wages and work opportunities (Bolsajian 2018; Adunts et al. 2019; Agadjanian et al. 2013). While much of the research is focused on understanding current migration patterns and its effect on the economy, there is little research that reveals motivation for migration or predictors for future waves of emigration. The data obtained from the Caucasus Barometer survey is unique in that it measures perception. In analyzing this data, we can see beyond the population who depend on emigration for survival, and instead more deeply understand the population who want to emigrate. A crucial distinction, this data shows that in addition to demographic qualities like age, gender, and language ability, an individual’s attitude towards the future and subjective qualities like personal values, hope, belief, and ability to envision a different life are all factors that contribute to emigration desire.

Data Analysis

All fieldwork data was recorded February 21,2020 to March 15, 2020 by the CRRC Armenia.

Age and Gender

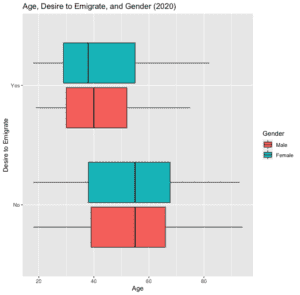

Not surprisingly, the population of people who want to leave Armenia is significantly younger than those who wish to stay. In 2020, the average age of the “Yes” respondents (both male and female) was just around 40, whereas the average age for the “No” respondents (both male and female) was 53.3, a difference of more than 10 years (Figure 1).

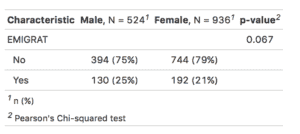

Looking at the breakdown of gender and emigration (Figure 3), a slightly larger percentage of males (25% of total) wish to emigrate than females (21% of total).

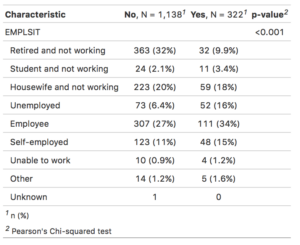

Employment and Job Satisfaction

When examining the employment status of respondents (variable EMPLSIT which asks “Which of the following best describes your situation?”), a larger population of those who wish to stay in Armenia are retired and not working, not looking for or wanting a job, or believe that they cannot start a new job in the short-term. On the other hand, a larger percentage of those who want to leave are in search of work. For instance, only 10% of the emigrant population is retired and not working, compared to more than triple, 32% of the non-emigrant population who are retired and not working. This data again emphasizes that age is a major factor in determining the respondent’s desire to emigrate (Appendix A).

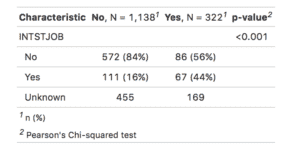

Further, only 16% of those who answered “no” to emigration are interested in finding a job (variable INTSTJOB which asks “Are you currently interested in a job, or not?”), compared to nearly triple the amount of those who answered “yes” to emigration. Not surprisingly, it can be gleaned that those who are interested in a job are more likely to want to emigrate (Appendix B).

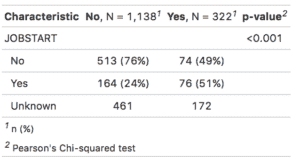

The desire to emigrate is not only linked to the individual’s search for employment, but also to one’s perceived ability to work (variable JOBSTART which asks “Would you be able to start working within the next 14 days?”). 76% of those who do not want to emigrate also stated that they cannot start a job within 14 days, while 24% stated that they could. For those who do wish to emigrate, it is more of an even split. 49% answered “no” to starting a job in 14 days, whereas 51% answered “yes” (Appendix C). Interest in emigration is strongly correlated with not only the desire, but also the ability to work.

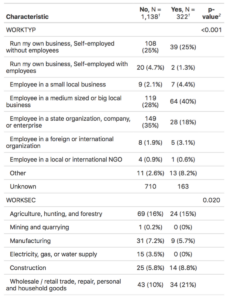

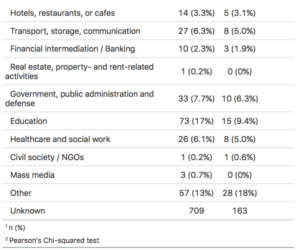

As far as work type and sector (variables WORKTYP and WORKSEC), data shows that respondents who have jobs that are connected to the country, or are benefiting from the state via employment and salary, have less motivation to leave. Among those who do work in a state organization, company, or enterprise, 35% did not want to emigrate, while only 18% did want to emigrate (Appendix D).

Job Satisfaction

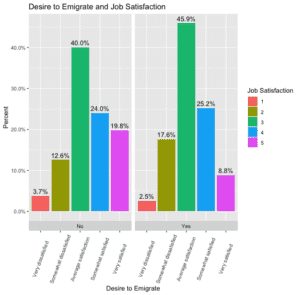

As seen in Figure 4 below, the majority percentage of people who do not wish to emigrate lie between averagely satisfied and very satisfied with their job (83.8%) whereas the majority percentage of people who do wish to emigrate are between somewhat dissatisfied and somewhat satisfied (89%).

Of those who do not wish to emigrate, 19.8% are very satisfied. Only 8.8% of those who wish to emigrate are very satisfied. On the flipside, of those who do want to emigrate, 17.6% are somewhat dissatisfied, whereas only 12.6% of those who would like to stay are somewhat dissatisfied.

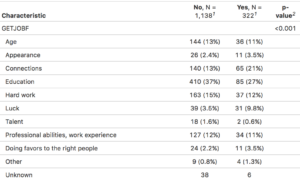

Indicators for Success

When asked about perception of qualities that would make someone most likely to get a job, there is a notable distinction between the emigrant and non-emigrant populations (Appendix E). Nearly triple the amount of those who wish to emigrate think that luck is the most important factor in getting a job (9.8%) compared to those who wish to stay (3.5%), whereas a higher percentage of the non-emigrant population think that education is the most important factor in getting a job (37% compared to 27% of the emigrant population). This may indicate that loss of faith in the education system is pushing Armenians to emigrate, or it shows an attempt to justify their challenges in finding a job within the country. Further, when comparing the two groups, a larger percentage of those who want to stay believe that hard work and talent can get you a job, whereas larger percentages of those who want to emigrate believe that connections and appearance are more important. This again shows that those wishing to emigrate have a distinct lack of trust in being rewarded for honest, hard work and conventional establishments like education in Armenia. Their larger trust in chance may also indicate a certain dream-like perception of the future.

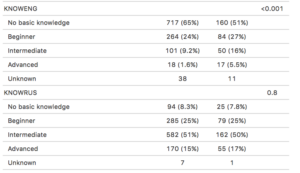

Language and Computer Ability

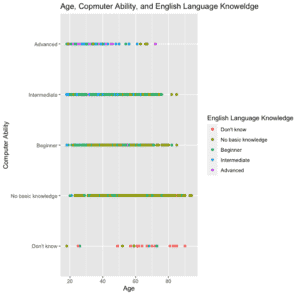

Having advanced English language ability (KNOWENG) is positively correlated with the respondent’s desire to emigrate (Appendix F). Theories in neoliberal globalization explain why and how English language skills as both a requirement and motivation for working, or more likely studying, abroad. International student mobility has risen in recent years. The number of international students more than doubled from 1998 to 2004 (Samers 2010). The overwhelming majority of students are concentrated in Anglophone nations, largely because of “the possibility of learning English combined with the perceived quality of higher education institutions in these countries, and the possible employment and settlement prospects that one might be afforded afterwards” (Samers 2010, p. 27).

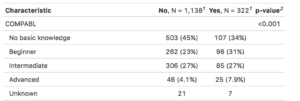

Thus the data reveals that no basic knowledge of English is negatively correlated to one’s desire to emigrate. The difference in language ability in Russian (KNOWRUS) was not a significant indicator of the respondent’s desire to emigrate. It is shown that higher computer ability (COMPABL) is also an indicator of desired emigration (Appendix F and Appendix G).

Looking at the graph below (Figure 5), English language ability is skewed towards the younger age demographic, as is having higher advanced computer ability. Older people have less English language knowledge and are more likely to state that they have ”no basic knowledge” of computers. This shows a more complete profile of the population who want to emigrate: those who are young, have higher English language skills, and are more computer savvy.

East vs. West?

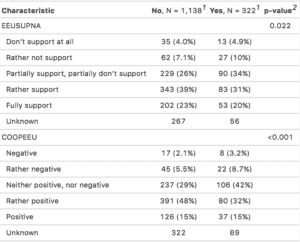

Support of the EEU was assessed by variable EEUSUPNA, which asks “To what extent do you support Armenia’s membership in the Eurasian Economic Union led by the Russian Federation?” Of those who want to emigrate, 48.9% either don’t support, rather not support, or partially do/partially don’t support the EEU. On the other hand, 88% of those who would like to stay in Armenia for good partially support, rather support, or fully support the EEU. When asked about the results of cooperation in the EEU (variable COOPEEU which asks “How would you assess the following processes for Armenia? Results of the EEU membership), of those who don’t want to emigrate, 63% answered positive or rather positive. Of those who do wish to emigrate, only 47% answered positive or rather positive.

According to this data, those who do not want to emigrate tend to lean more towards supporting Armenia’s involvement with Russian led organizations like the EEU, possibly showing that those who do want to emigrate feel stronger pull towards places with more Western ideologies.

Relationships Abroad

Having close friends or relatives abroad is a large indicator of potential emigrants. Because Armenians have such a large Diaspora network, they have a bigger chance at emigrating successfully. A network abroad minimizes spending and encourages people to leave the country. This falls in line with the well documented Migration Network Theory.

In a 2004 paper published in the IZA Discussion Paper Series, researchers discussed the influence that networks and friends have on potential migrants and motivation to emigrate:

“Networks are an important element in lowering costs of migration. Both networks and herds play a very important role in decision-making regarding the choice of location of migration. People go to where they have information. One type of information is the information one obtains from looking at what others do. Even more important, perhaps, what we show is that people want to migrate with friends (herds).” (Epstein et al. 2004, p. 12).

In the Armenian context, seeing first-hand examples of friends or family living abroad may make the possibility of emigration seem more realistic or enticing. It is also possible that family members abroad are encouraging those who are still in Armenia to leave.

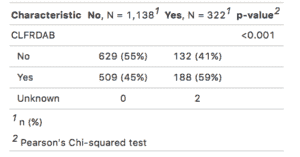

It is therefore unsurprising that of those who wish to emigrate, 59% have a close friend living abroad as opposed to the 45% of those who don’t wish to emigrate. Close friends abroad and desire to emigrate are strongly correlated in this data (Appendix I).

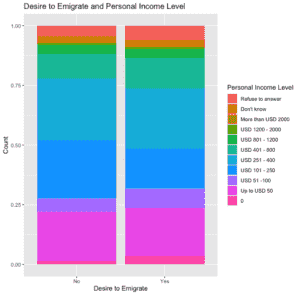

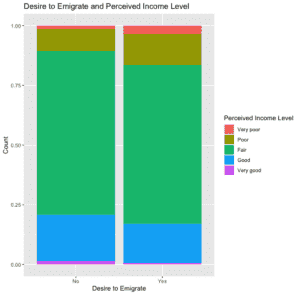

Economic Status and Income

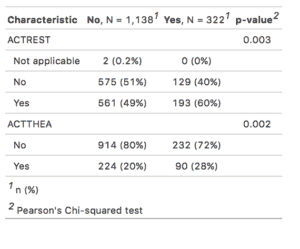

Interestingly, the variable measuring personal wealth (PERSINC) is not significantly correlated with the emigration variable. That said, other measurements of wealth and perceived wealth, such as how frequently the household goes to restaurants (ACTREST) or sees a movie in theaters (ACTTHEA), are correlated with one’s desire to emigrate. In this data, having recently attended a theater or cinema is positively correlated with the desire to emigrate (Appendix J). Of those who wish to emigrate, 60% answered that they went to a restaurant in the last 6 months whereas only 49% of non-emigrants had gone to a restaurant. Despite actual income or perceived income, the individuals wanting to emigrate show a higher interest in culture, luxury, or comfort.

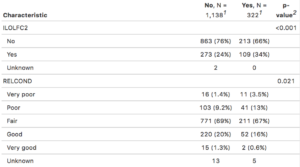

Although personal income level is not a statistically significant indicator of emigration, perceived income tells a different story (variable RELCOND, which asks “Relative to most of the households around you, would you describe the current economic condition of your household as …”). 21.3% of respondents who don’t want to emigrate consider their relative condition good to very good, whereas only 16.6% of those who do wish to emigrate consider their situation good or very good. 16.5% of those who want to emigrate consider their position poor or very poor whereas 10.6% of those who don’t want to emigrate consider themselves poor to very poor (Appendix K). Perceived economic situation is strongly correlated with the emigrant variable. Not surprisingly, those who perceive themselves in worse situations are more likely to want to emigrate. Again we see how perception plays a huge role in whether or not someone wants to leave Armenia.

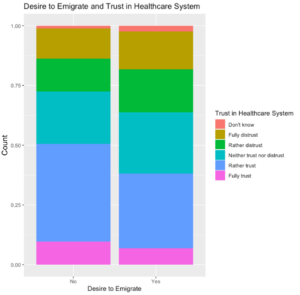

Trust

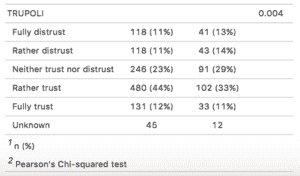

People who tend to have less trust in institutions such as the medical system and the army wish to emigrate, whereas people with more trust wish to stay (Appendix L). For instance, of those who wish to stay, 50.9% either rather trust or fully trust the healthcare system (TRUMEDI). Of those who wish to leave, only 39% rather or fully trust healthcare, and a larger portion compared to the non-emigrant population, 35%, fully distrust or rather distrust healthcare. The trust in the army is also strongly correlated with desires to leave. 91% of non-emigrants compared to 84% emigrants either fully or partially trust the army (TRUARMY). Additionally, those who wish to emigrate have significantly lower trust in parliament, the executive branch, and the police than those who wish to stay (TRUPARL, TRUEXEC, TRUPOLI).

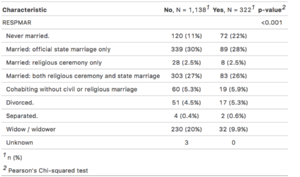

Marriage

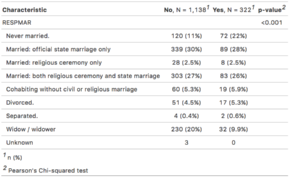

Attitudes towards gender and marriage appear to have correlations with emigration as well. 22% of those who wish to emigrate were never married. This is double the amount of those wishing to stay, 11%, who were never married (Figure 9, Appendix M).

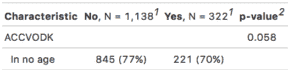

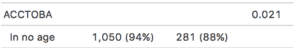

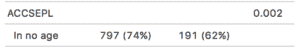

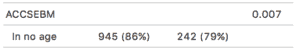

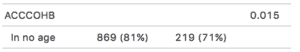

When asked questions about women’s rights, such as from what age is it acceptable for a woman to drink strong alcohol, smoke tobacco, live separately from parents, have sex before marriage, and cohabit with a man without marriage (ACCVODK, ACCTOBA, ACCSEPL, ACCSEBM, ACCMAR, ACCOHB), in each category, a higher percentage of those who do not wish to emigrate answer “in no age” (Appendix N). A higher percentage of those who wish to stay believe women at no age should be allowed to do any of the following above activities, except get married.

As for marriage, the population who does not want to emigrate believe that women should get married at an earlier age (Appendix N). All variables listed above are strongly correlated with the desire to emigrate. In this sense, it can be argued that those who want to stay have more traditional gender values, and those who wish to leave have more progressive opinions. This makes sense when we look at the generational divide and take into account that those wishing to leave are typically younger, but it is again interesting to consider when trying to understand what is pushing young people to leave Armenia.

Conclusions

The Caucasus Barometer is a survey designed to measure public perception. This is uniquely interesting in studying the topic of migration in Armenia because it can reveal defining characteristics of those who are looking to leave Armenia for good, or potential migrants. While the survey does not explicitly ask why people want to emigrate, the data can be analyzed to draw inferences about this population.

Potential migrants are primarily young and looking for work opportunities abroad, educated in English, more tech savvy, come from parents with higher education, and generally have more progressive attitudes towards women.

Overall, the data shows that those who are wishing to leave are not amongst those who perceive themselves to be among the lowest income group. This is likely because those on the perceived lowest rung of the economic ladder cannot imagine a future of emigration. The population wishing to leave are also not among the highest perceived income group, nor most economically successful, nor involved in the work related to government. In this regard, the profile of those wishing to leave seems to be a middle-ground population: those who have not yet reached grand success in Armenia but have enough exposure, motivation, or desire to expand beyond Armenia’s borders. The data shows that the wish to emigrate isn’t only linked to desires, ambition, and ideology, but also perceived feasibility, i.e., whether or not the respondent feels that a future of emigration is within the realm of possibilities. If not, the respondents tend to be more likely to want to stay in Armenia.

Many complex economic, social, and political systems are contributing to the migration crisis in Armenia. Lack of high quality education and employment opportunities for young people presents a major challenge to encouraging the youth population to stay. This ‘brain drain’ phenomenon is well documented in Armenia. Young people who want to receive a good salary and pursue careers in the fields in which they study tend to look for better opportunities abroad. The problem, however, is that university diplomas in Armenia do not always translate abroad. Wage differentials are also motivating young people to leave. According to a 2020 World Bank report, employed migrants earn nearly double the amount in foreign countries than they do in Armenia, where “the average monthly wages were 500 USD versus less that 250 USD earned by their counterparts employed in Armenia” (Honorati et al. 2019, p. 3).

Given this information, more research that attempts to understand the psyche of potential migrants could be helpful in creating targeted programs and policies that reverse the growing trend. On the flip side, certain targeted programs such as better English language courses and more advanced technological training may also appeal to this population and increase the likelihood that they stay in the country. If Armenia wants to retain its bright, talented, and motivated youth population, however, the nation must continue to grow economically and culturally. For example, by improving employment opportunities in sectors that appeal to young educated people, increasing educational programs, and funding cultural activities that entice and engage youth, Armenia can address the emigration issue on a national scale. Examples of worthy investments might include paid fellowships and internships for early-career workers, creative opportunities for youth, access to more public art and gathering spaces, better transportation infrastructure, building more youth networks, and other programs that may help retain the young and motivated population. In doing so, people might begin to see a hopeful future for themselves in Armenia.

References

1. The survey has not been implemented in Azerbaijan since 2013

Bibliography

Adunts, D., Afunts, G. (2019). ‘Seasonal Migration and Education of Children Left Behind: Evidence from Armenia.’ CERGE-EI Working Paper Series No. 641.

Agadjanian, V., Sevoyan, A. (2013). Embedding or Uprooting? The Effects of International Labour Migration on Rural Households in Armenia. International Migration Vol. 52 (5).

Avagyan, L. (2021). Armenia’s Deepening Demographic Challenge: Covid-19, Artsakh War Compound the Problem. Hetq.

Barsoumian, N. (2013). To Greener Shores: A Detailed Report on Emigration from Armenia. The Armenian Weekly.

Bolsajian, M. (2018). ‘The Armenian Diaspora: Migration and its Influence on Identity and Politics.’ Global Societies Journal. Vol. 6

Caucasus Research Resource Center (CRRC) – Armenia (2020). Caucasus Barometer 2019 Armenia [Data set].

Epstein, G. & Gang, I. (2004). The Influence of Others on Migration Plans. (IZA Discussion Paper No. 1244). IZA.

European Training Foundation (ETF) and Caucasus Research Resource Center (CRRC) – Armenia (2012). Migration and Skills in Armenia: Results of the 2011/12 Migration Survey on the Relationship Between Skills, Migration, and Development. European Training Foundation.

Gevorkyan, A., Gevorykan, A., & Mashuryan, K. (2008). Little Job Growth Makes Labor Migration and Remittances the Norm in Post Soviet Armenia. Migration Policy Institute.

Honorati, M., Kerschbaumer, F. & Yi, S. (2019). Policy Brief: Armenia: Better Understanding International Labor Mobility. The World Bank.

Manke, M. (2011). Enhancing Migration Data Collection, Processing and Sharing in the Republic of Armenia: Needs Assessment and Gap Analysis Report. International ORganization for Migration Mission in Armenia.

Mejlumyan, A. (2022). Out-migration in Armenia increasing. Eurasianet.

National Statistical Service of the Republic of Armenia (ARMSTAT) (2018). Migration Snapshot of the Republic of Armenia – 2018. Armstat.

National Statistical Service of the Republic of Armenia (ARMSTAT), World Bank (2018). Armenia Integrated Living Conditions Survey (ILCS) 2018, Ref. ARM_2018_ILCS_v01_M.

Samers, M. (2010). Migration (Key Ideas in Geography). Routledge.

Vidal, E. (2019). Migration Data in the Context of the 2030 Agenda: measuring migration and development in Armenia. International Organization for Migration.

World Population Review. (2022). Armenia Population 2022 (Live).

Appendix

All tables are created by the author using data from the Caucasus Barometer and correlations are evaluated using Pearson’s Chi-squared tests.

Employment

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

Appendix D

Indicators for Success

Appendix E

Language and Comp Ability

Appendix F

Appendix G

East vs. West

Appendix H

Relationships Abroad

Appendix I

Economic Status and Income

Appendix J

Appendix K

Appendix K

Trust

Appendix L

Marriage

Appendix M

Women’s Rights

Appendix N

The author’s attitudes, opinions, and conclusions expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect the views of the CRRC Armenia.