On December 12, 2022, at around 10:30 a.m., a group of Azerbaijanis, dressed in civilian clothing and posing as “environmental activists”, blocked the Goris-Stepanakert Highway which, as stipulated in the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh Trilateral Statement, passes through the Lachin corridor, connecting Artsakh (Nagorno-Karabakh) with Armenia and the outside world. On April 23, 2023, Azerbaijan announced the installation of an illegal Azerbaijani checkpoint at the Hakari River Bridge along the Goris-Stepanakert road. On April 28, so-called Azerbaijani “environmental activists” reported their withdrawal from the blocked section of the road, to be replaced by representatives of the Azerbaijani police and other services. From June 15, the peacekeepers’ transit was forbidden for ten days, too. From June 25, the operation of the ICRC resumed: however, medicine importation and transportation of medical personnel into Artsakh remained prohibited. Peacekeepers were also prohibited from providing essential food and other goods.

The ongoing blockade, entailing the physical obstruction of the only corridor, has left Artsakh’s population of 120,000, including 30,000 children, in a state of absolute isolation, causing massive violations of individual and collective human rights, as well as multifaceted existential and security threats.

Concurrently, Azerbaijan is deliberately disrupting the regular functioning of Artsakh’s vital infrastructures: gas supply, electricity supply, and communication networks. This deliberate action intensifies the already severe humanitarian crisis and inflicts further suffering on the population of Artsakh.

On September 19, 2023 Azerbaijan unleashed another large-scale aggression against the people of Artsakh. These military operations represent the continuation of the blockade commenced on December 12, 2022. New developments unfolded in Artsakh following the meeting between the representatives of Artsakh and Azerbaijan in Yevlakh on September 21…

Blockade of Artsakh: Starvation, Genocide Threat, and Hope for Survival

“Inadu (Out of Defiance)” podcast | Episode 1

The authors of the podcast are Nina, a teacher and a blogger, and Shogher, a presenter and an actress. Through this podcast, they represent the life in blockaded Artsakh from the first day to the present reality; they share their concerns, emotions, and expectations. They have chosen this way to communicate the situation in Artsakh more vividly, Nina explains: “The pace of events is so rapid and there is so much to say thatno televised program, Instagram post or article can truly reveal what exactly is going on.”

When Shoger first learned about the blockade, she was not in Artsakh, but in Armenia, preparing to go on tour to Europe: “At that time I didn’t fully comprehend the gravity of the situation and that it would last this long… I thought it was just another provocation”. After completing her tours, Shogher applied to the Red Cross to return to her homeland and succeeded with lots of difficulties: “I can no longer imagine leaving Stepanakert because I am afraid I may never be able to return home.”

At that time, Nina was in Artsakh. Even within the borders of Artsakh, the news was initially received as commonplace : Azerbaijanis once again temporarily closed the road and cut off the gas supply. “For the first 10 days, no one was particularly worried. Journalists from outside Artsakh were calling, expressing their desire to come and shoot documentaries about the blockade; but for those of us living here, life continued as usual, as if nothing strange happened.” Everyone was confident that the road would soon be opened, given the presence of peacekeepers.

But after a while, we even experienced emptiness in stores, the coupon system ceased to function either: “there was absolutely nothing in stores. How could one be in need of buying food in the 21st century?” It was cold as the gas supply was cut off.

They had no way but to endure it. In Artsakh, education has faced challenges for several years, first because of the coronavirus, then the war, and now the blockade. Nina, the teacher, explains: “If we hadn’t gone to school and made an effort, our children would have been deprived of education for 3 years. It appears to me this was Azerbaijan’s intention. Our lessons lasted only 20-25 min: the children simply listened to the teachers and returned home.”

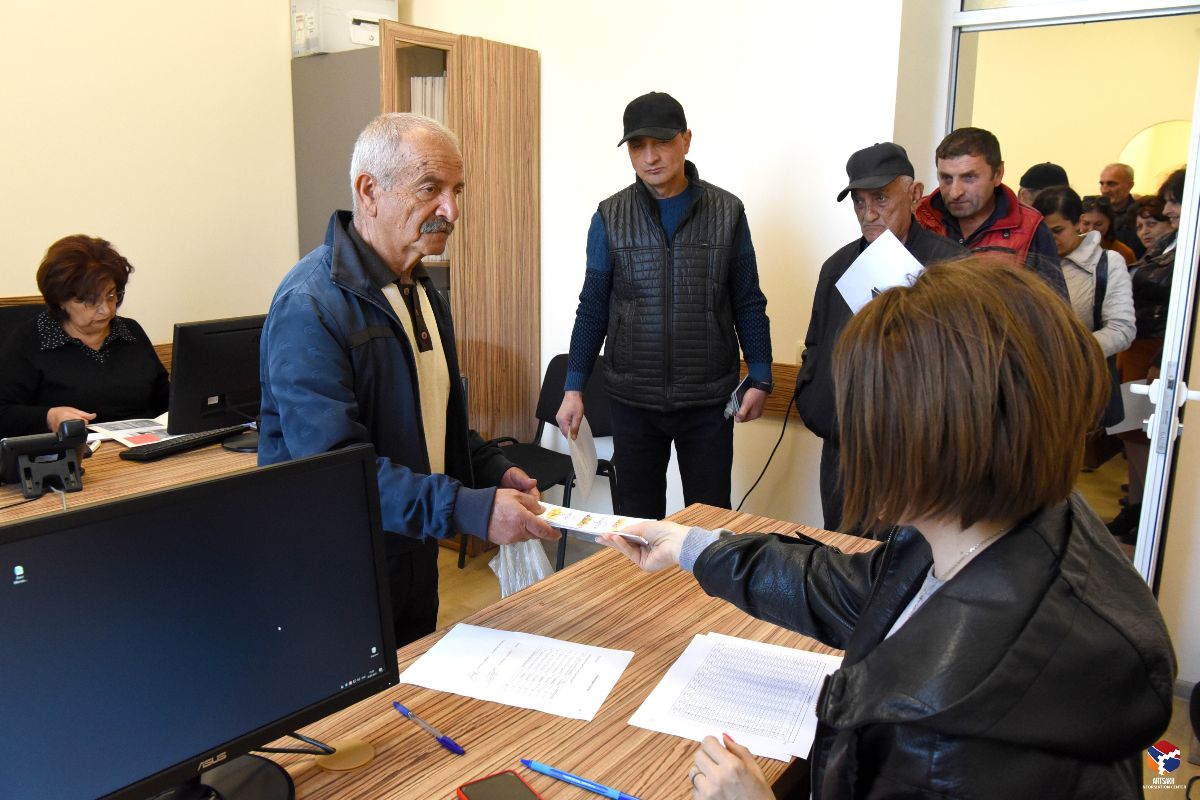

Some time later, the coupon system began to operate. Peacekeepers transported a limited amount of food to Artsakh: some managed to obtain food after waiting in long queues for hours, while others remained empty-handed even after those hours of waiting. As they put it: “you had to struggle to secure 1 kg of macaroni.” In addition to these, another great obstacle in meeting daily needs, going to work, and tending to small gardens for supplementing the food shortage was the lack of fuel.

The blockade seemed to have become a part of their “normal” life. In mid-spring, they thought the road would soon be opened. But on April 23, 2023, Azerbaijan declared the installation of an illegal Azerbaijani checkpoint on the Hakari bridge along the Goris-Stepanakert road. After that, the situation deteriorated: “We thought it was the peacekeepers who were in control of the situation, but at the moment, neither we nor they are in control, but our enemy.”

Since June 15, the Russian peacekeepers’ movements were also forbidden. Since June 25, after a 10-day blockade, the International Committee of the Red Cross has resumed its operations along the Lachin corridor, but peacekeepers were still prohibited from delivering food and other essentials. Since July 11, Azerbaijan has also prohibited the ICRC from importing medicine and transporting patients to Artsakh: “Everything has changed significantly, including people’s attitude. No matter how hard you try to concentrate on your work, family, self-development, you fail, as the harsh reality consumes both your energy and time.”

Living under the blockade is much harder for families with children. It’s necessary to go to work, do the household chores, and at the same time, ensure that the children aren’t stressed by the situation. The new generation is unaccustomed to such restrictions, having grown up in freedom compared to the previous generation that endured the “dark and cold” years.

Shogher recounts a story about the life under blockade: “A child was watching a cartoon and saw one of the characters eating a banana:

-Mum, I want a banana.

-There isn’t one, darling, there are no bananas.

-Mum, I want one.

-I told you, dear, please.

-Ah, ma, I really want it.

-That’s enough. Don’t ask again, there are no bananas, and there won’t be one.

The child gazes at the mother for a while and says, “then, please, change the cartoon so at least I don’t have to see it.”

The sad part is being deprived of the opportunity to choose. Nina explains: “People might assume we’re focused on eating bananas, but no, the problem is not that we want to eat it every day or we ate it when life went on normally. It’s more of a psychological issue – having the choice whether to eat a banana or an apple or neither… in fact, you can live without a banana, but it’s what reminds us that we’re not free, we’re not living our usual lives, that it’s others who make decisions on our behalf…”

Despite the blockade and its consequences, life in Artsakh is going on, people continue to do their jobs: “There are no justifications for not going to work, despite the blockade, the lack of transportation means… Instead, there is a strong desire to live, to keep going. People aren’t just sitting in total depression and idleness, they’re not feeling entirely desperate or unwilling to take action. On the contrary, they try to do even more.”

How come you don’t leave Artsakh? What makes you still live and see your future there?

Shogher: “Out of defiance (Arm. “ինադու” – out of defiance). This situation serves as clear evidence that they need to put in more effort to force me out of my home and my homeland. And the more difficult they make our lives, the stronger ourdetermination grows to stay here out of defiance of them, to live better, and to be happy.”

Nina: “Out of defiance (Arm. “ինադու” – out of defiance), as I realized we’re writing our history, we’re parts of that history. I don’t desire a moral victory but I want a real one. I want to tell my children how we struggled and how we fought for a better life, and not the story of our departure because staying was hard. Yes, it was bad and I had to fight out of spite to everybody, out of defiance to Azerbaijanis who wanted us to leave.”

Authored by Mariam Manukyan

Translated by Iveta Avagyan

Inadu (Out of defiance): Blockade of Artsakh: Starvation, Genocide Threat, and Hope for Survival

The material is published with the consent of the “Inadu” podcast authors, Nina Shahverdyan and Shogher Sargsyan. The original videos are published on the YouTube page of “Inadu”. The textual and visual representation and translation of the publications are carried out by “Enlight”.

You can support the “Inadu” podcast on Patreon through this link.

Read other publications about the Artsakh issue and the blockade in the Artsakh Chronicle.