Historical Overview

In 1988-1990 the Azerbaijani people comprising the majority of the region of Vardenis in Armenia left their residences. In formerly Azerbaijani populated villages numerous Armenians settled who had left Azerbaijan SSR. Before the flaring of the conflict the Azerbaijani people comprised the ethnic majority of the region of Vardenis (about 70%). On the local level the Armenians of the region were divided into two social-cultural groups: Yaylakians (that is a Turkish word which means a person engaged in cattle breeding in high-mountain pastures) who, in accordance with the Treaty of Turkmenchai in 1828, were resettled in that region, and migrants, who were the resettlers that barely escaped the massacres of 1895-1915 in the Ottoman Empire. It is interesting that these groups comprised comparatively stable communities, difference between which was mainly displayed in daily communication. Up to 1988 the local Azerbaijani people and the Yaylakians were higher in the social rank than the migrants. It is best manifested in the pejorative nickname “Gyalma” (in translation from Turkish the word means a new comer) given to the migrants. The structure and stratification of the social groups were radically changed when as a result of the difficult process of change of the structure of the population in the region, the Armenians became the majority of the population. Henceforward the label “Gyalma” was ascribed to the Armenian emigrants from Azerbaijan.

In the beginning of the 1990s because of the worsening of the social-economic conditions (the earthquake of Spitak, the Collapse of the USSR, Artsakh War) the relationships between the “locals” and the “emigrants” were obviously aggravated, thus moving into a new platform and obtaining the definitions of familiar and strange. According to the field data (08.2014-01.2015, village Mets Masrik, region of Vardenis) during the first years of resettlement in the differentiation between the familiar and strange such criteria as the notions “emigrant” and “local” (yaylakian, emigrant) played their unique role. Today in the relationships of the two groups social-economic criteria as education, social state, presence of relatives abroad, etc., have a crucial role. However, this does not at all mean that the conflict between the “emigrant versus local” has disappeared altogether. That phenomenon is still topical, but there is no sharp emphasis as during the 1990s.

Thus, the aim of the research is to reveal the ways of origination of the possible problems during the adaptation in a new environment and integration processes, as well as to reveal the ways of their solution. Similar researches can be viewed as research directory for avoiding the sharp angles in subsequent difficult integration processes.

Appropriation of Physical Space

Before 1988 the localities in Vardenis region that were inhabited by Armenian-Azerbaiajni mixed population, were divivded according to the principle of ethnic identity. Thus, the village Mets Masrik (even though it was considered one administrative unit) was divided into two parts by the central rural road, where the Armenians and the Azerbaijani people lived separately. In the Armenian-Azerbaijani shared localities the relationships between the two ethnic groups were neighbourly tolerant. Those were relationships formed exclusively on economic basis (agriculture, nomadic breeding), that did not encourage marital relations. Extremely rarely those relationships could turn into ties of blood.

Since 1988 many Armenian refugee families have started to settle rural houses that previously belonged to the Azerbaijani people. The resettlement was of both planned (that is to say it was organized by the village councils) and spontaneous (by separate families) characters. In those localities where a full and organized resettlement took place via the exchange program of the villages, frequently the work position and the social state were maintained. Consequently, the refugees, in addition to the Azerbaijani houses, received a model of some social-cultural relationships (everyday experience, social relations, housekeeping skills, etc.) that had been developed by the former ethnic groups of that region for decades. For the locals the strangeness of the refugees was conditioned not only by the fact of the resettlement from Azerbaijan, but also by their settlement in the Azerbaijani part of the village, which naturally was a cause for the locals to ascribe them hostility, strangeness, and the state of “Azerbaijanism”.

The resettlement of the Armenians from Azerbaijan was mainly of individual character. The process of appropriation of the abandoned houses and localities began earlier than the settlement of the Armenians in Armenia. In the beginning of 1988 the first wave of Azerbaijani refugees fled to Azerbaijan from the southern regions of Armenia. When it became clear that the conflict between the two republics was only flaring up, the Azerbaijani started looking for houses (apartments, localities), aiming to exchange their property with the Armenians living in Azerbaijan. That phenomenon was gradually obtaining larger volumes: the Armenians and the Azerbaijani were ubiquitously exchanging houses, signing contracts, composing documents concerning the exchange of the real estate, selling and buying new houses. This process, undoubtedly, created favourable conditions of resettlement for both parties, as many families knew in advance where they were to move to. They could agree or reject the the suggested exchange and search a more beneficial variant. Very often people with their families went to see the apartment they were going to exchange with, got acquainted with the locality, with the dwellers of the village and their lifestyle.

Interlocutor (I. from now on) – in 1988 the Yerevan-Getashen route was still operating. After the resettlement we have also gone there for several times and brought back the property left.

Author (A. From now on) – How the process of finding an apartment for resettlement was going?

- – The Azerbaijani were coming to learn the addresses of the Armenians from the regional condominiums, then were visiting and offering us to make an exchange, they were presenting the conditions, then leaving their addresses and going away. We could freely come to see the house, accept or reject it. Our family moved to the new place without a preliminary visit to see the conditions. At first we made an exchange with an owner whose house later turned out to be old and tumbledown. We returned it back and made an exchange with this current house.[i]

On the Armenian-Azerbaijani border, in the town of Ghazakh, a whole group of so-called middlemen (Armenians, Azerbaijani, Russians, Lezgins), the activity of which was the following: to find the former inhabitants from both sides after the resettlement, to formulate documents of property exchange, to organize safe transportation of families and their estate, etc.

(I.) – When the municipality of the village wanted to dismiss us from the house we occupied, we went to the town of Ghazakh located on the Armenian-Azerbaijani border, where the close contact between the Armenians and the Azerbaijani people still was maintained, and with the intercession of various people we could find the owner of this house. By paying him 15000 roubles we legally bought it (Field Work, Vardenis region, village Mets Masrik, 15.08.2014).

(I.) – Two Azerbaijani Lezgins, who pledged to safely deliver us up to the border, transported us along with our property in two cars, and we pledged to guarantee their safe transfer in Armenia, though nothing threatened them here[ii].

The process of resettlement took place gradually: in three years representatives of both sides were coming and going, transporting the property, formulating the documents, selling houses, continuing to take care of the graves, etc. It lasted until both republics- Armenia and Azerbaijan almost wholly got rid of the representatives of undesirable ethnic groups.

In the first years of the resettlement the refugees started to intensively master, transform the physical space that was new to them and where they had to settle.

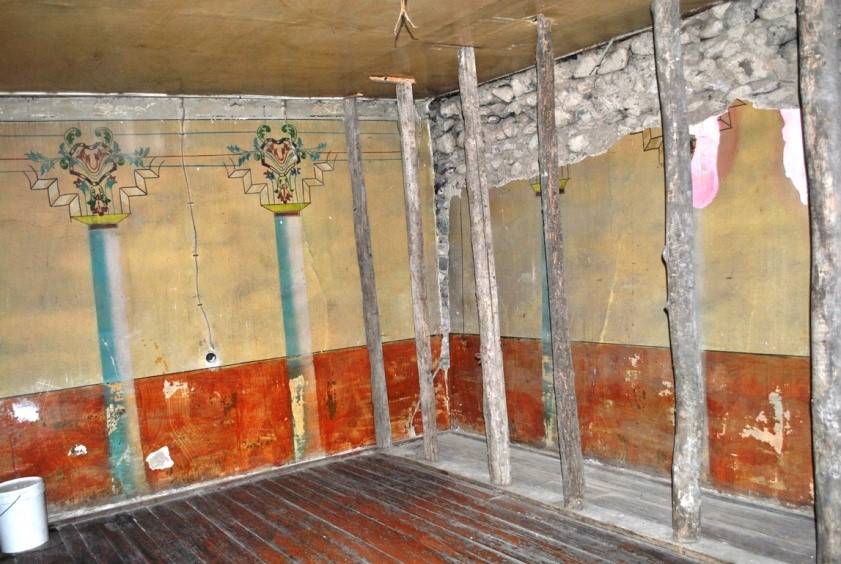

First of all the resettlers started to change the inner form of previously Azerbaijani houses. They replaced the glazed covered balconies with stone walls (in Mets Masrik the previously Azerbaijani houses were uniform, i.e. the house consisted of two parts (drawing room and bedroom) and an adjacent covered balcony with a main entrance, and as for the bathroom and the kitchen, they were frequently presented as separate structures), the large halls of the houses which were designed for drawing rooms, were divided into smaller rooms, the walls were painted in lighter shades (in Azerbaijani houses the walls were mainly of darker colours-red, green, blue), the metallic railing banisters which were characteristic to the local Azerbaijani houses, were removed. All the subsequent reconstructions were connected to the existing concepts of comfort and cleanliness. During the interview extremely rare were the expressions that were directed to the absolute rejection of the house of a “stranger, enemy” (destruction, reconstruction). There are still some houses in the village that have undergone no change for a quarter century, and have maintained their initial “Azerbaijani” interior (picture 1.).

The reconstruction of the houses was also conditioned by the fact that the houses and the buildings allocated for the economic management were partly dismantled by the former owners and local Armenians during the emigration and immigration: in most of the houses the window glasses were broken, the doors, the window frames, and the roofs were removed.

During the resettlement the majority of the houses were fairly empty, as the Azerbaijani refugees had taken the large part of their property with them.

(I.) – In that period there were rather many unoccupied houses, and the resettlers could choose where to settle in. Even the local inhabitants were able to privatize the empty houses due to their acquaintances and relatives. Some houses were in really poor conditions. For instance, the walls of my neighbour’s house were all cracked, and he had to reinforce the walls from all the sides. When my family moved here in December, 1988, the windows and the doors of the house were missing, and we had had to live in a neighbour’s house for about a month[iii].

In the beginning of the 1990s, many houses and buildings were solely abandoned or used not according to their initial function. Thus, the living houses were frequently converted into enclosures, hen-coops, granaries, and storehouses. Those houses, which were not used, during the course of time were dismantled and sold as building materials, or were robbed by the locals.

(I.) – The dismantling of the houses took place in mutually beneficial conditions, both for the refugees and the authorities of the local regional centre. When the refugees moved in, they needed building materials for repairing the houses. Well, they were stealing those materials from the abandoned houses, for which they paid a penalty of 60 roubles. The local Armenians were doing so either. It was very convenient, and many houses were pulled down in that way[iv].

Even today, a quarter century later, the houses resettled by the refugees have not been accepted by them as «their own/appropriated/suitable for living». Some refugees took steps to make changes (add and rebuild buildings), create «homes» in accordance with their ideas about comfort, where they could start a new life. However, almost all the buildings were generally left to their initial shape. This observation can have several explanations. Often the physical space, and the house, in particular, can become a subject of emotional charge, in the context of which one’s “own” (former) locality is viewed as “more quiet and convenient place to live in, where a person has goals and ambitions. The houses and localities acquired by the refugees after the resettlement were perceived as unfavourable for living. The new apartments were put in comparison with the places of exile, where the hopes of future blew up.

(I.) – There is no hope. This place resembles a camp designed for prisoners of war[v]. – We came to «hell» from «heaven». How can I insist that I feel at home here?[vi] – When we came and saw such amounts of snow in the mountains we had the impression as if we had been exiled to Siberia [vii].

The collective memories of the resettlers about their “little homeland” will apparently disappear together with their bearers. Likewise, perception of a “good” abandoned house creates in an individual the impression of staying in the new apartment temporarily, and naturally they do not have any desire to build their future in the new place.

(I.) – Is it possible to live like that? We seem to live in a station with the eternal expectation of resettlement[viii].

The memories of familiar cities, and villages, which the refugees had to abandon, as a rule are full of nostalgia and sadness. Especially for the elder generation the differences between the conceptions of “now – here” and “then – there” are very contradictory. “Everything was much better, happier, and meaningful there, here everything is much worse, meaningless, prosaic”. The emphasized negative attitude towards all the changes that took place (be it weather, the taste or smell of water, or the climate) is being formed on the contrary to the once «rich – their own» economy, in the context of memories of the property earned by sweat and lost by the irony of fate.

(I.) – You had to see what a tumbledown and dirty kindergarten my child did go to. In Baku he attended a prestigious kindergarten, which was one of the best. When we arrived he did not know a word in Armenian, and he was four then. We did lose everything! I had an apartment with three rooms, luxurious by the standards of that time. I had a high paying job, and the salary of my husband was simply magnificent for that time[ix].

For many the difference between the concepts of «good» and «bad» is formed based on the memories of the relative social prosperity during the soviet years. The forced resettlement and the subsequent collapse of the Soviet Union left their mark in the memories of both the refugees and the local Armenians. The deteriorating living conditions, which were the result of the collapse of the Soviet Union, were perceived by many as phenomena closely related to the resettlement.

(I.) – When the Soviet Union collapsed the local Turks left[x], and at the same time a big wave of refugees flooded, with whom the elder generation of the local Armenians could not get on. They blamed the refugees for the deterioration of the living conditions and used to repeat; «We lived well enough with «our» Turks, but after the arrival of the refugees everything collapsed». But the problem was not conditioned by the leaving of Azerbaijani people from Armenia at all, but by the collapse of the Soviet Union, the war, deepening of economic crisis[xi]. That is to say the irrevocable «loss» of the micro world that had been created by them and their ancestors, caused grave sufferings to both sides (resettlers and those who had to accept them).

The individual memory concerning the abandoned familiar house was expressed in subconscious level either. As many refugees say, in their dreams they see the former localities only, which is a distinctive manifestation of memories about their «own» houses.

(I.) – In my dreams I only see the way of living, the house, that we left there. I never see this house. I see Kirovabad, Khanlar, but never this village[xii]. These all are memories of our childhood. I spent my childhood in the village of Chadakhlu, and naturally, in my dreams I see my native village, the childhood I spent there. But, alas, nothing can be brought back (his eyes are in tears, he shakes his hand, and leaves)[xiii].

Generalizing the above mentioned, we can state that by the fusion of different cultural constituents the new social image of the refugees was defined and characterized, which also was expressed in the newly obtained apartments (in the redistribution and rebuilding of the houses and localities, etc.) The cultural peculiarities regarded as standards, which characterized the existing social-structural border between the Armenians and the Azerbaijani, in the course of time were reflected in the relationships of the representatives of two Armenian groups – the locals and the refugees. This phenomenon had its manifestation in the symbolic domain (tombs, local sanctuaries, etc.) too, which even more emphasized the controversy of those relationships.

[i] Field Work (from now on FW), Vardenis region, village Mets Masrik 10.08.2014 [ii] FW, Vardenis region, village Sotk, 23.08.2014 [iii] FW, Vardenis region, village Mets Masrik 11.08.2014 [iv] FW, Vardenis region, village Sotk, 23.08.2014 [v] From the field materials of Petrosyan G., research program-workshop which was carried out by the scientific-research center “Azarashen” in 1988-1999 [vi], FW, Vardenis region, village Mets Masrik 02.08.2014 [vii] FW, Vardenis region, village Mets Masrik, 04.08.2014 [viii] FW, Vardenis region, village Mets Masrik, 04.08.2014 [ix] FW, Vardenis region, village Mets Masrik, 25.08.2014 [x] In the spoken Armenian the Azerbaijani (Caucasian Tatars) are called Turks, based on the fact that they speak Turkish, and thus resembling them to the Turks of Turkey. [xi] FW, Vardenis region, village Mets Masrik, ,07.08.2014 [xii] FW, Vardenis region, village Mets Masrik, 10.08.2014 [xiii] FW, Vardenis region, village Mets Masrik, 02.05.2014References

Author: Eviya Hovhannisyan © All rights are reserved. Translator: Lilit Maghakyan.Bibliography