Read the first part here.

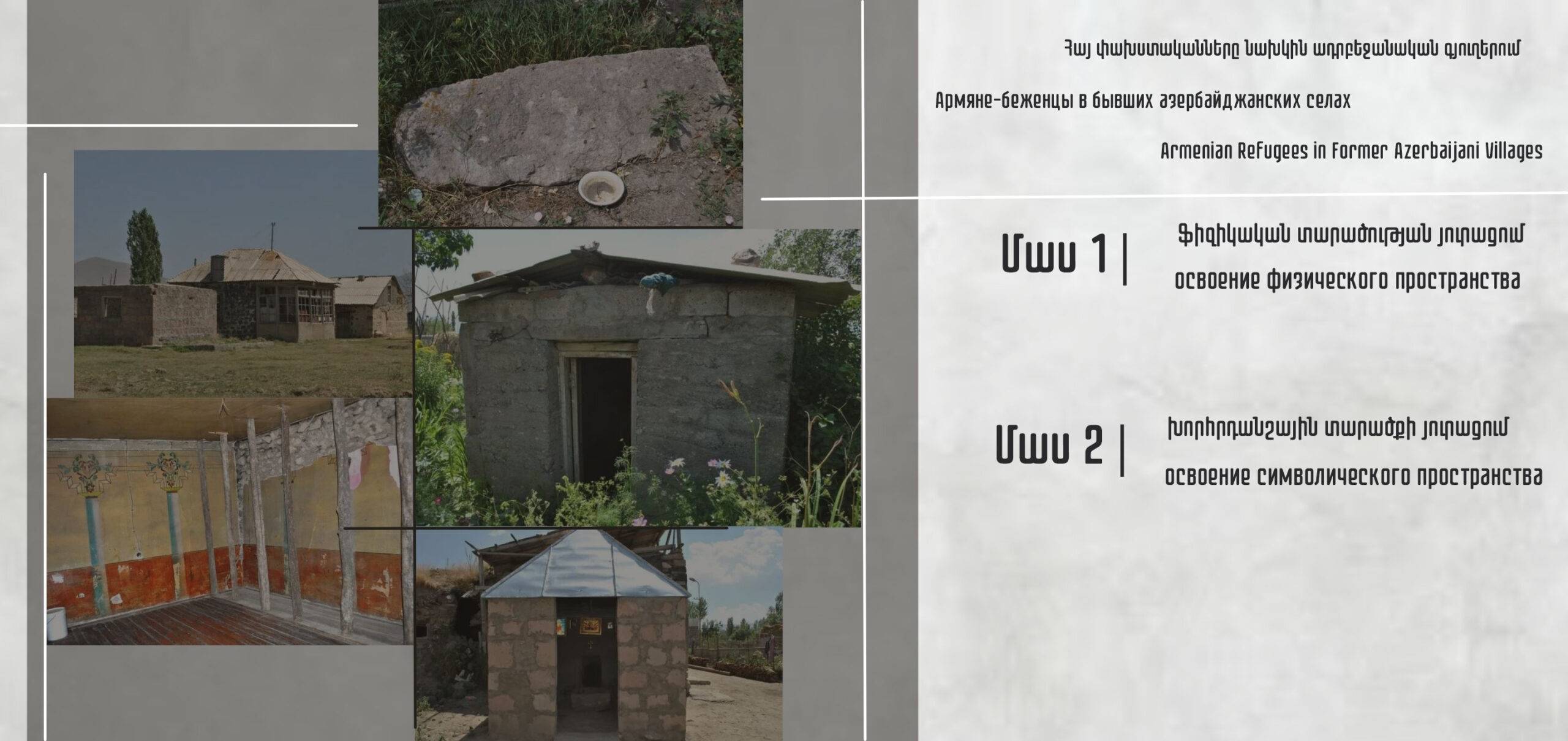

Transformation of territory of cultural “foreign” and building of new syncretic identification can be viewed with the example of changes made in the symbolic area of former Azerbaijani settlements (cemeteries, local sanctuaries, etc.) Both the residential area of the village and the nearby cemeteries before the resettlement were divided into Armenian and Azerbaijani parts. It was conditioned by the two ethnicities belonging to different religions, respectively, Christian and Muslim. The new cemeteries of refugees began to appear in the territory of former Azerbaijani settlements at some distance from Azerbaijani cemeteries, on the opposite side of the village of Hachats. After moving to Great Masrik, the refugees began burying their dead in a separate part of the local Armenian cemetery, and in the neighboring village of Sotk a separate cemetery was built for refugees. In the early years, for appropriation of symbolic territory refugees were bringing soil for their burials from the graves of their relatives in the former villages. In the newly built cemeteries of refugees one can find gravestones and names of the people who died in Azerbaijan because some were bringing complete graves. In refugee cemeteries you can see gravestones with pictures of previous inhabitations, panoramas of abandoned villages, pictures of houses.

“My brother’s grave remained in Khanlar. Until the last day my mother did not want to leave Khanlar. My brother died at a very early age, my mother did not want to leave his grave, she kept repeating: how can I leave my child’s grave? When my parents died in Armenia, I asked them to put my brother’s picture on the gravestone of my father and mother. ” (Vardenis region, the village of Great Masrik, 04.08.2014).

The experience of construction of cemeteries has also been brought. Thus, refugee graves are often surrounded by metal fences, often buried in a grave metal cross. A modest metal cross is often put on the grave: this is an unusual experience for local Armenians.

The Azerbaijani cemeteries are completely forgotten. Often on the gravestones of the Azerbaijani cemeteries of the Great Masrik and Sotk villages traces of vandalism can be seen, a practice that is typical of conflict areas (broken gravestones with traces of firearms, digged-removed eyes, etc.). It is interesting to observe how the idea of being holy of any symbol contributed to the preservation of Azerbaijani tombs. Thus, the vandals did not touch the gravestones on which the scriptures were made in Arabic letters. The incomprehensible Arabic script was not linked to the Azeris, and the stones on which the inscription was made by Cyrillic were broken and desecratedi. The existence of separate “foreign” cemeteries in former Azerbaijani villages shows the peculiarities of the occupation of the village territory after resettlement period. The Azerbaijani cemeteries were not considered possible areas for burial after death of resettled Armenians, those are noted as places of burial for “enemies and heterodox people” as “foreign” or not “own” memory and culture territories.

Apart from modern cemeteries, there are many medieval gravestones in the territory of Great Masrik. Today local stories and ritual traditions in the territory of the village Great Masrik, are one of the ways to define a certain social balance between refugees and the local population. Here we have to talk about not so much about massive religious beliefs as to the internal and external social factors which determine the peculiarities of the daily life of the studying society.

The village itself was founded in XIV-XVI centuries. In its territory khachkars has been preserved which are dating back to the IX-X centuries, and on which writings testify to the existence of the settlement in that time. Mazra reached the peak of prosperity in the 14th-16th centuries when it became the residence of Melik-Shahnazarov’s dynasty. The center, western and north-eastern part of today’s settlement was built in the medieval cemetery area where scripts, khachkars and gravestones were preserved dating to the IX-XVII centuries.

There are many stories widely spread among village inhabitants about how the gravestones were found in the village. Usually these are testimonies in the form of conversations or even a description of the details of the historical-cultural image of the village.

“Without this cross, this stone was fallen in the midst of our field, it was hindering during the agricultural work. We moved it here. And it (the stone) tells us, I’ll punish you, why did you move me? Then my 15-year-old boy died. It (the stone) tells me that I will make you suffer so much that you do not know how it happened.” ii (pic. 1)

This topic is closely related to the so-called question of “ancestors worship and animism”, the “purity” of the dead – “uncleanness,” “sanctity,” and “cruelty” as well as with the categories of “godliness” – “atheism”, “patronage” / “non-patronage” applied to the local population. According to the stories of residents of the Great Masrik, during the pre-conflict period, “the local Azeris treated respectfully and somehow with fear towards medieval Armenian gravestones on which ones crosses were depicted.” The fact that old graves become objects of worship and function as rural sanctuaries indicates the typological proximity of that phenomenon to the worship of “unknown” sanctuaries, when the randomly discovered tombs become a subject of national piety and worship, gaining a crown of holiness.

It is important to take into consideration that old graves represent a quite unique element of the cultural panorama. On the one hand, they are some of the substantive testimonies of a small number of local history, on the other hand, statues have certain functions as well as due to the secondary ritualization and myths in the current life of the villager. For ritualization secondary subjects in a specific area codes of traditional national culture activities and vocabulary are important which are later applied to everyday processes. After the sanctuary goes through “common use,” its symbolic status becomes complicated and reflects in many stories and ritual traditions.

The “socialization” of the sanctuary inevitably leads to the rise of competition among individual families or communities, as well as local ritual professionals (fortune-tellers, quacks) who pretend to control the sanctuary. Thus, modern experiences of (re)interpretations and (re)ritualization create a new social reality. During implementing field studies, you often have to face the fact that most information providers avoid applying to the past as an object description principle. For many tradition bearers, explaining what an “element” of an image is, means telling them what is accepted to do in that place (for example, how the worship ritual of the local sanctuary is created, or what happened here with someone (stories about “miracles”, visions, etc.). Such experiences in the studying field mainly affected the fact that there is no common micro-historical memory for the Armenian population and refugees from Azerbaijan, and the attitude towards religious traditions varies greatly among these groups. Thus, the consequence of the anti-religious policy of the Soviet Republic was not the elimination of religious traditions, but the rebuilding. As a result, for local residents (Armenians) in the Great Masrik, religion became homely, domestic, passed almost entirely under the control of women and was reorganized to communicate with the deceased and local sanctuaries. The Armenians who moved from Azerbaijan had their local perceptions of Christian religiosity and traditions. For example, those who escaped from the Azerbaijani Dashkesan and Khanlar regions, on the third Sunday of each August of the year performed a great pilgrimage to the “Saint Pand of Pand Mountainiii“, which is now in the district of Dashkesan. To the Holy Pand’s pilgrimage people were coming with full families, sometimes with complete villages for participating in celebrations and sacrifices, relatives and fellow villagers were coming from Baku, Yerevan, Kirovabad and other cities. After moving to Armenia by force and after closing the borders of Azerbaijan, Armenian refugees were deprived of their historical pilgrimage place. In the new and unusual environment of religious culture, the Armenians of Azerbaijan over time began to adopt the local “laws” of religious customs and beliefs of the sacred stones (which they sometimes call “Pand”). Often the traditions and stories of refugees about the local idols and saints are in the context of a local religious discourse, which is complemented by a discourse typical to Armenians of the Azerbaijani environment. “The chapel on this holy stone was built by the previous owner of the house – an Azerbaijani. She told us that the soil under this stone has healing properties, it is necessary to mix that soil with the warmth of tonir (oven, erected in the ground), salt and water, and put it on the wound like this (she shows) and the pain will certainly pass … we do sacrifices to our saint on the third Sunday of August, Pand day. According to our custom, we call the sanctuary Cross, and the locals call it Holy”iv. (Pic. 2)

This quotation from the interview with a woman who fled from Azerbaijan is a striking example of how the process of stratification of religious every day and historical traditions, stories, art samples, discourses occurs in one area. This proves that the historical memory of collective is not the reflection of historical facts in the consciousness of the culture holders, but is determined as a dynamic process of meaning formation which is in conformity with present reality. Local traditions and ritualization make sense to different objects around the world. Due to the fact that those meanings are appropriated, stories somehow condition the choice of cognitive, narrative and behavioral strategies. There is a competitive struggle of local worshipers in the village, which, in its turn, finds symbolic reflection in stories where the sacred object or certain superpowers independently define the rules of religious conduct by directing people to who, where and how to perform appropriate religious activities. About such sanctuaries in local Armenian stories usually talk about dreams or visions, where a person was required to prepare this or that belief object (usually called “shushpa”, old, ancient icons, embroidery cloths, crosses of wood or clay, etc.) and sacrifice to the “saint”. The status of a local sanctuary is directly related to the belief in its magic power (treatment of diseases (infertility, faints, moles), salvation from death (house collapse, etc.). “A few years ago we lived in this house (he’s showing a half-destroyed house). At night in my mother’s dream the saint visits and says, “I cannot keep the heaviness of walls of this house anymore.” At that moment my mother wakes up and escapes with my grandmother out of the house, and at that moment the house collapses. In this way our “holy” saved us. ” v Formation of similar anti-intuitive performances, according to Boer’s thought, has a special potential for attention and consequently promotes the isolation of ceremonial norms, actions and symbols. National religiosity is a test area, where normative touches the emotional one (hereafter, the emotional tension and dramatization of those experiences), where unlike the institutional religion, often the religiosity of women dominates, where the perception of religious texts varies with certainty and being literally (sometimes with more extreme eschatology and inclination towards miracle), but where, at the same time, improvisation and pragmatism are typical of experiences, where the basic regular, written story is mixed with small local and, as a rule, verbal stories. Comments by refugees, the religious traditions described in the video, their normative and sensory perception of the newly acquired “ritual space” played a major role in the integration process in the new social environment.

Thus, the stories written more than two decades ago after moving to a new area, not only shed light on these people’s past, but also show the results of their adaptation and integration both in the physical and symbolic areas. These memories form a new social space for the regions where refugees from Azerbaijan were densely resettled. The process of appropriating of “new” residential areas took place simultaneously with the process of formation of social borders between the social area and, in particular, between the refugees and the local Armenian population.

I In1929 the Latin alphabet (“yangalif” ) was approved for writing in Azerbaijani. It was a Soviet policy to reduce the influence of Islam in the Turkic republics, which until 1929 used Arabic script without exception. ii Village of Great Masrik, Jule 2014, “Holy Stone – Ankhach”. iii “Pand” is a short version of the Saint Pantaleon. He’s a Christian saint who is worshiped as a great martyr, a healer, a doctor who does not require a payment. The commemoration is held on July 27 in the Orthodox churches on the Julian calendar. St. Pantaleon was one of the most beloved saints of Albania in the early Middle Ages. According to E. Lalayan’s historical information, “The monastery of St. Pantaleon was built on the hilltop of the mountain with the same name … At the place where a small domed chapel now stands there was a large monastery in the past with church brotherhood. Only today people go there on the Assumption holiday of the Virgin Mary for pilgrimage.” iv Village of Great Masrik, Jule 2014, “Holy Stone – Holy Cross”. v Village of Great Masrik, Jule 2014, “Holy Stone – near Margo’s house”.References

Bibliography

Author: Evia Hovhannisian © All rights are reserved.

Translator: Anna Zakaryan.